Frontline Learning Research Vol.5 No. 4 (2017) 1

- 41

ISSN 2295-3159

University of Leuven, Belgium

Article received 9 March / revised 21 July / accepted 27 Augustus / available online 16 October

The current gap between traditional team research and research focusing on non-strict teams or groups such as teacher teams hampers boundary-crossing investigations of and theorising on teamwork and collaboration. The main aim of this study includes bridging this gap by proposing a continuum-based team concept, describing the distinction between strict teams and mere collections of individuals as the degree of team entitativity. The concept entitativity is derived from social psychology and further developed and integrated in team research. Based upon this concept and core team definitions, the defining features shaping teams’ degree of entitativity are determined: shared goals and responsibilities; cohesion (task cohesion and identification); and interdependence (task and outcome). Furthermore, a questionnaire is developed to empirically grasp these features. The questionnaire is tested in two waves of data collection (N1=1,320; N2=731). Based upon a combination of Classical Test Theory analyses (exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses) and Item Response Theory analyses, the questionnaire is developed. The final questionnaire consists of three factors: shared goals and cohesion, task interdependence, and outcome interdependence. Further psychometric analyses include the investigation of validity, longitudinal measurement invariance, and test-retest reliability. This manuscript describes frontline research by: (1) developing a new conceptualisation transcending the variety in terminology and definitions used in team and group research by creating a shared language and opening up team research to non-strict teams and (2) combining two methodological traditions regarding questionnaire development and validation (Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory).

Keywords: team; team entitativity; questionnaire development; Classical Test Theory; Item Response Theory

As collaboration and teamwork appear to be indispensable in the current society and organisational life, ample research has focused on the investigation of teams or groups and their processes in order to gain insight into how employee professional development and performance can be improved (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson, 2008; Sundström, McIntyre, Halfhill, & Richards, 2000). Research on collaborative processes shows a large diversity in types and structures of collaboration and the terminology that is used to describe them. These include for example group, team, network, community of practice, and professional (learning) community. The latter are especially prevalent in the educational context as the educational counterpart of the learning organisation concept proposed by Senge (1990). While the traditional and archetypically defined team concept is more common in research in industry and organisations, educational research tends to focus on more flexible concepts such as communities. Both seem to be mostly separated streams of research: Research in schools rarely includes frameworks that were developed and elaborately investigated in traditional team research and the latter tends to neglect teacher teams and collaboration. Team research tends to focus on a specific type of team, meeting strict criteria included in team definitions such as the one suggested by Cohen and Bailey (1997) (e.g., Decuyper, Dochy, & Van den Bossche, 2010; Edmondson, 1999; Mathieu, Heffner, Goodwin, Salas, & Cannon-Bowers, 2000; Salas, Burke, & Cannon-Bowers, 2000). They define a team as an interdependent collection of individuals, sharing responsibility for the outcomes of the team, who both see themselves and are seen by others as a social entity (i.e., a team) that is part of a larger social system (such as a business unit or organisation). However, in practice not all teams meet these definitions and they are not always teams in the strict sense of the word (such as teacher teams). Despite the increasing importance of team and collaborative work in schools, team researchers tend to keep away from this context because teacher teams often do not fit traditional team criteria, which hampers a straightforward application of team theories and frameworks. At the same time, research on the topic of teacher collaboration tends to investigate this phenomenon more or less in general rather than to focus on more deep-level quality features and dynamics of such collaborative endeavours. Moreover, it is prone to lacking both conceptual and methodological rigour: The terminology and conceptualisations of different types of teacher collaboration are often ill-defined (Vangrieken, Dochy, Raes, & Kyndt, 2015) and literature on teacher collaboration tends to be criticised for its lack of methodological rigour (Crow & Pounder, 2000). In line with the recommendation of Wageman, Gardner, and Mortensen (2012), these gaps indicate the need for a flexible definition of a real team. Wageman et al. (2012) stress the value of being able to transfer insights and approaches developed in team research to new kinds of collaboration. In order to make this possible, there is a need for a new and continuum-based team concept.

This study aims to tackle these gaps by (1) introducing a continuum-based conception of a team and (2) making this continuum measurable. Addressing the first aim, this study introduces the concept team entitativity to bridge the conceptual gap between real teams and other types of collaboration that are not strict teams. Team entitativity refers to the teamness of a team or the degree to which a group of individuals meets the criteria of a team. The conception and definition of team entitativity is based upon a combination of two mostly separated streams of research (research on group perception and research on team dynamics). Crossing the boundaries between team research and research on teacher collaboration by introducing a more flexible team concept could be very beneficial for both fields, expanding the scope of traditional team research and strengthening the rigour of research on teacher collaboration. In order to reach the second aim, a questionnaire was developed. This makes it possible to measure the conceptual gap and to empirically bridge research on teams and other groupings which was not done before. In a first step towards bridging these fields empirically, the psychometric quality of the team entitativity instrument was assessed in the context of teacher teams in secondary education in Flanders (Belgium).

As suggested earlier, teacher teams are often excluded from traditional team research because they mostly do not meet the strict theoretical team definitions (Smith, 2009; Vangrieken, Dochy, Raes, & Kyndt, 2013). Elements such as interdependence appear to be difficult to achieve in teacher collaboration and teacher teams tend to operate more as aggregates of individuals bonded by social ties, focusing on psychological safety and social cohesion (Moolenaar, 2010; Ohlsson, 2013; Smith, 2009; Vangrieken, Dochy, & Raes, 2016). In these cases, teacher teams operate as co-acting groups in which members believe to work in a team but actually work in ways that do not match the basic notion of teamwork (Lyubovnikova et al., 2015). The core of their job, teaching, is mostly performed individually in their classroom. ‘Egg-crate schools’ characterised by teacher isolation in classrooms and the accompanying culture of individual work, together with teachers’ preference for individually exercised autonomy may withhold a collaborative, teaming culture to take shape in education (Gajda & Koliba, 2008; Lortie, 1975, in Westheimer, 2008; Somech, 2008).

Related to the complexity of realising teacher teamwork in its fullest form, there is a grey area surrounding teacher teams. The construct does not appear as uniform but it takes different forms and shapes. Vangrieken et al. (2013, 2015) present a comprehensive teacher team typology attempting to provide an overview of these different possible forms. As such, teacher teams can have different tasks that range from a focus on policy-making and school-level decisions (e.g., governance/management, innovation and school reform) to teamwork focused on classroom education, teacher professional development, and problem-solving (e.g., instruction, pedagogy, teacher learning). These different tasks entail a different level of depth of collaboration: While a focus on a mere material or practical task involves only superficial discussions, teams working on improving instruction or teacher learning entail more deep-level discussions of teachers’ practice and pedagogical beliefs or motives. Furthermore, teacher teams can be organised in different ways: disciplinary or interdisciplinary, within or cross grade levels, and long term or temporary. In practice, this often creates a complicated structure of various teams and sub-teams in schools. For example, in (Flemish) secondary schools teachers are mostly organised in disciplinary subject departments or teams (cross grades). Especially in bigger schools, these subject departments sometimes consist of different grade-level subject teams (teachers who teach the same subject in the same grade). However, in smaller schools – and especially in primary education – the whole teaching staff may be organised in one overarching team. This focus on whole-school collaboration can for example also be found in literature on professional (learning) communities (e.g., Birenbaum, Kimron, & Shilton, 2001; Leonard & Leonard, 2001). A final dimension derives from the fact that the construct teacher team presents itself as a continuum, ranging from completely individualised teacher work to teamwork in its fullest form (Smith, 2009; Vangrieken et al., 2015). Hence the team entitativity construct is especially valuable in this context to capture this collaborative continuum.

The first part of this study focuses on defining team entitativity. Starting from the origins of the entitativity construct in social psychology research (Campbell, 1958), the concept is further developed and integrated in team research.

‘Entitativity’ resides from Gestalt Theory and social psychology and was originally introduced by Campbell (1958) who defined it as “the degree of being entitative. The degree of having the nature of an entity, of having real existence” (Campbell, 1958, p. 17). He focused on the analysis of social aggregates as entities and on explaining why some groups are considered real groups and others mere aggregates of individuals. The construct received resonance in different studies on group perception yet still remained unclear in definition, leading to a variety in the way entitativity is interpreted, defined, manipulated, and measured (Hamilton, Sherman, & Castelli, 2002).

In order to categorise this variety in the use and interpretation of entitativity, a distinction along two axes can be made: On the one hand a distinction between an outsider and an insider perspective and on the other hand a focus on essence or agency. The first axis defines a distinction proposed by Yzerbyt, Corneille, and Estrada (2001). An outsider perspective focuses on non-group members’ (outsiders) perceptions of the degree of entitativity that a collection of individuals has. Originally, entitativity focused on outsider perceptions as it was coined by Campbell (1958) to investigate the way people use available information cues to assess the extent to which an aggregate of individuals has the quality of being an entity or a group. These information cues were derived from the principles of Gestalt theory and include proximity, similarity, common fate, and pregnance (good continuation or good figure). Hence the focus was on visual cues that can be observed by outsiders who are not part of the entity. As opposed to the outsider perspective, studies including an insider perspective focus on properties of the group, as they are experienced and perceived by the members themselves (Carpenter et al., 2008; Jans, Postmes, & Van der Zee, 2011). These are not necessarily observable by non-group members. The extent to which these properties are perceived to be present is presumed to indicate the group’s degree of entitativity. For example, Carpenter et al. (2008) ascribed the fact that some groups are more group-like than others to the perceived degree of cohesion, unity, interdependence, conformity, and fit between group members. From an insiders’ perspective, Jans et al. (2011) criticised the proposition that similarity - a core aspect of entitativity in an outsider perspective - is a key predictor of perceived entitativity and argue that within-group differences do not necessarily hinder a sense of cohesion and unity.

The issue of whether or not similarity is a key predictor of entitativity brings us to the next axis defining a distinction between essence and agency (Brewer, Hong, & Li, 2004; Rutchik, Hamilton, & Sack, 2008). Essence theory perceives entitative groups as being characterised by a fixed and inherent shared essence (Brewer et al., 2004). The criterion of similarity is the source of groupness, as group perception is based on members sharing certain properties (Jans et al., 2011). The focus is on innate fixed personality traits of group members and this perception can mostly be found in social cognitive research on stereotypes (e.g., Crawford, Sherman, & Hamilton, 2002; Yzerbyt et al., 2001). Opposed to this static meaning of entitativity, agency theory proposes a dynamic view in which entitativity is based on perceived common goals and intentions of groups (Brewer et al., 2004). The nature of the group and its boundaries are no longer perceived as static but malleable and changeable over time. Dynamic properties (e.g., shared goals and coordination) are to a lesser extent formal organisational structures; instead they refer to psychological states and relationships among group members (Brewer et al., 2004). In this dynamic perspective, similarity of group members is not needed to perceive a group as an entity (Jans et al., 2011).

Research on entitativity rarely focuses on work groups, but often investigates large social entities, such as for example race or nationalities (e.g., Castano, Yzerbyt, Paladino, & Sacchi, 2002; Dasgupti, Banaji, & Abelson, 1999; Yzerbyt et al., 2001). Some studies investigate a broad array of entities, ranging from a family, a committee, to people at a bus stop or even as broad as women as a category (e.g., Crawford & Salaman, 2012; Hamilton et al., 2002; Svirydzenka, Sani, & Bennett, 2010). This study further develops the construct for application in research on work groups and teams and as such introduces team entitativity.

3.2.1 Teams-in-theory: Defining a team

In order to clearly conceptualise team entitativity as the degree to which an aggregate of individuals is a team, it needs to be clear what it means to be a team. However, in team literature (a lot of) different definitions are used. Katzenbach and Smith (1993) define a team as “a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable” (p. 45). A similar and integrative definition was proposed by Cohen and Bailey (1997):

A team is a collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for outcomes, who see themselves and who are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more larger social systems (for example, business unit or the corporation), and who manage their relationships across organizational boundaries (p. 241).

Similarly, Hackman (2012) defined teams as:

Intact social systems whose members work together to achieve a common purpose. They have clear boundaries that distinguish members from non-members. They work interdependently to generate a product for which members have collective, rather than individual, accountability. And they at least have moderate stability, which gives members time to learn how to work well together (p. 437).

Integrating these definitions, a team can be defined as “a distinguishable collection of individuals, who identify themselves as a team and interact as a team to reach certain shared goals for which they share responsibility and hold themselves mutually accountable. Members are jointly committed to the common purpose and task and are interdependent in their tasks and outcomes” (Vangrieken et al., 2015).

Often the terms team and group are used interchangeably, both in research and practice (Lyubovnikova, West, Dawson, & Carter, 2015; West & Lyubovnikova, 2012). However, in this study they are considered to be separate constructs. While they do partially share the same characteristics – they are delineated social units working in larger organisations – they are not the same concepts (Main, 2007). The main difference between both includes the fact that the term group is more broadly used and defined: All teams are groups but not all groups can be called teams, as they do not always meet all criteria included in team definitions (Van den Bossche, Gijselaers, Segers, & Kirschner, 2006; Vangrieken et al., 2015). While a team needs to meet certain criteria included in the definition provided above in order to actually be a real team, groups do not. The concept group in itself can have a variety of meanings and is used to refer to different entities that strongly vary in their properties (Hamilton et al., 2002). Groups can be broadly defined as collections of individuals that share a common social categorisation and identity (Raes, Kyndt, Decuyper, Van den Bossche, & Dochy, 2015). The term is often used in definitions of various social categorisations, such as communities of practice (CoP) or professional learning communities (PLC). In these cases, the definitions add criteria that need to be met in order for a group to be called a CoP or PLC. In conclusion, the term group is mostly used as an umbrella term capturing different possible social categorisations. In this study, a team is defined as one specific subtype of a group meeting certain team-criteria.

3.2.2 Towards a continuum-based team concept: Team entitativity

Previous team research already started to challenge the universal use of the team concept, distinguishing real teams from for example co-acting groups (Lyuobovnikova, West, Dawson, & Carter, 2015) or pseudo-teams (West & Lyuobovnikova, 2012). However, these conceptions still refer to a black-and-white categorical interpretation: Teams are real teams or pseudo-teams. However, as suggested by Wageman et al. (2012), changes in the environment of teams (e.g., increasing virtual and globally dispersed work and collaboration) challenge the boundaries of the traditionally defined team. Rather than using defining features as delineators to distinguish real teams from non- or pseudo-teams, it is valuable to investigate these features as dynamic constructs in their own right (Wageman et al., 2012). Hence, team entitativity is proposed here as a concept that is worth investigating as a separate variable. It is introduced as a dynamic characteristic of teams and how team members themselves perceive their team. In line with entitativity literature, teams are presented as a continuum. Collections of individuals or groups possess a degree of team entitativity, which is dynamic in nature. A team’s perceived degree of team entitativity is dynamic and malleable, depending on for example time, team development, and contextual influences. This is in line with the conception of groups as social systems that are dynamically engaged with their contexts (Hackman, 2012; Wageman et al., 2012). Hence, when positioning our conceptualisation of team entitativity on the essence – agency axis described earlier, it matches the latter perspective.

When discussing the features that determine whether a group of people is a real team, different aspects are mentioned. These include (structural) interdependence, shared objectives, team reflexivity, boundedness (i.e., it is clear who is part of the team and who is not), and stability of membership (Buljac, Van Woerkom, & Van Wijngaarden, 2013; Lyubovnikova et al., 2015; Wageman et al., 2012; West & Lyubovnikova, 2012). In a changing society and environment for teams, the meaning and importance of these features may have changed. For example, in globally dispersed teams the boundaries of team membership may not be that clear and the fact that people tend to be part of multiple teams and the existence of complicated multiteam systems consisting of different teams and subteams may challenge the criterion of stable team membership. Moreover, supposedly structural team features such as structural interdependence (i.e., residing from the design of work itself) are actually dynamic phenomena that are increasingly in the hands of the team members themselves (Wageman et al., 2012). Hence, an important characteristic of the teamness of groups or teams includes that it strongly resides from choices and perceptions of the members themselves. West and Lyubovnikova (2012) also suggested asking the individual team members to what extent the core characteristics of a team are present. Thus, regarding the insider – outsider axis of entitativity, the focus here is on an insider perspective starting from how members themselves perceive their team.

Furthermore, because of our focus on work teams rather than social entities (such as families) our definition of team entitativity is task-focused. The latter can be seen as a core characteristic of work teams (Salas, Bowers, & Cannon-Bowers, 1995). Work teams can be categorised as common identity groups that focus on attachment to the group as a whole, based upon identification with the group, its goal, and its purpose (Sassenberg, 2002). The task focus and the fact that members are brought together to complete shared goals distinguishes them from for example groups of friends. The latter are described as common bond groups that are focused on interpersonal attachment between group members based upon positive attitudes towards other members (Prentice, Miller, & Lightdale, 1994; Sassenberg, 2002). Hence, the focus here is not on these groups that focus on (social) interpersonal attraction but on task-focused work teams in which attachment is based on a common goal and purpose. Previous research found mixed results concerning the effects of certain social aspects (e.g., social cohesion) on team functioning, not always finding beneficial outcomes (e.g., Van den Bossche et al., 2006; Lima, 2001). This supports our focus on task-related rather than social aspects of teams.

3.2.3 Defining features

The degree of team entitativity a collection of individuals possesses, is determined by the degree to which different defining features of a team are present. The defining features included in the conceptualisation put forward here are derived from the aforementioned team definitions and the most prominent criteria rising from entitativity literature (Campbell, 1958; Carpenter et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2002). Three main features of team entitativity can be distinguished, acting as forces binding team members together in a task-focused team: (a) having shared goals and responsibilities, (b) cohesion, and (c) interdependence among team members.

Shared goals and responsibilities. Entitativity literature uses common goals and outcomes, shared purpose, and common fate as criteria or cues for the degree of entitativity (Campbell, 1958; Carpenter et al., 2008; Crawford & Salaman, 2012; Hamilton & Sherman, 1996; Lickel et al., 2000). Furthermore, to be defined as a team, groups of individuals have to share common goals (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993; Kozlowski & Bell, 2003). Moreover, highly entitative teams are characterised by a shared responsibility of the members for the goals and outcomes to be reached and for the required team process (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Katzenbach & Smith, 1993). Members of these teams hold themselves mutually accountable for the common goals (Katzenbach & Smith, 1993). Thus in case of high levels of team entitativity, members have to reach a shared outcome in the team and have predefined team goals. The team is held mutually accountable for the attainment of these goals or outcomes and the team process by which they are reached.

Cohesion. The degree of cohesion is a second defining feature of entitativity (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2008; Cavazza, Pagliaro, & Guidetti, 2014; Spencer-Rodgers, Hamilton, & Sherman, 2007). Sometimes entitativity is even reduced to cohesion (Hamilton, 2007). Group cohesion is defined as the result of all the forces that bind members to each other and to their team and act upon members to stay in the group (Festinger, 1950; Guzzo & Shea, 1992). Festinger (1950) suggests three components of cohesion: (a) attraction to the group (i.e., interpersonal attraction or social cohesion), (b) task commitment (i.e., task cohesion, extent to which individual goals are shared with or enabled by the group), and (c) group pride (i.e., members experiencing positive affect from being associated with the group) (McLeod & von Treuer, 2013). The first component relates to the interpersonal conception of group cohesion – based on mutual positive attitudes among members - that is the origin of attachment in common bond groups such as groups of friends (Sassenberg, 2002). As the focus of this conceptualisation is on work teams and task-related aspects, this interpersonal or social cohesion was not included. What binds members of a common identity group – such as a work group - is not this interpersonal attraction but a focus on identification with the goal and purpose of the group (Sassenberg, 2002). Hence, the focus here is on the two other components suggested by Festinger (1950): task cohesion (cf. task commitment) and identification with the team (cf. group pride).

Task cohesion includes the degree of shared commitment among members to achieve a goal that can be reached solely by the collective efforts of the group (Van den Bossche et al., 2006). Carron (1982) defined cohesion as “a dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its goals and objectives” (p. 124). Hence, in the case of a high degree of team entitativity, teams are characterised by a shared commitment to the tasks of the team, the latter acting as the force that holds team members together.

The second aspect of cohesion, identification with the team, includes on the one hand the degree of identification of the members with the team and on the other hand the degree to which team members feel that (membership of) the team is important for their job. Both aspects are seen as important features determining the degree of entitativity (Crawford & Salaman, 2012; Lickel et al., 2000; Meneses, Ortega, Navarro, & de Quijano, 2008). Similarly, high levels of team identification and perceptions of being part of the team are important features of a team (Smith, 2009). Team identification can be defined as “awareness and attractions towards an interacting group of interdependent members, by self-identified members of that group” (Bouas & Arrow, 1996, p. 155-156). As the focus is on the task, the importance of the team to its members is defined here as the perceived degree of importance of team membership and team tasks or goals to members with regard to their job. Thus, in the case of a high degree of team entitativity, team members experience a sense of affinity with their team and perceive membership as important for their job functioning.

Interdependence. A third defining feature includes the degree to which team members are interdependent. Different authors investigating entitativity describe interdependence as an important criterion (Carpenter et al., 2008; McGrath, 1984). Moreover, working interdependently is a key characteristic of teams (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Kozlowski & Bell, 2003). In short, interdependence means that team members do not only depend on their own actions but also on the actions of other members in order to perform their tasks or reach certain outcomes (Weick, 1976). Wageman (1995) argues that interdependence can originate from different sources: task inputs (e.g., skill distribution, resources), work processes, the way goals are defined, and the way performances are rewarded. Van der Vegt, Emans, and van de Vliert (1998) distinguish between task and outcome interdependence in an attempt to capture these different sources of interdependence. The common task or goal of teams can vary and can be of a different nature. While the focus here is on work teams (i.e., teams that are brought together to perform certain work-related tasks), people can also be collaborating with a focus on a specific aim for learning. The latter are mostly referred to as communities of practice (CoP) or professional learning communities (PLC) and are more often found in the educational context compared to business (DuFour & Eaker, 1998; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Vangrieken, Meredith, Packer, & Kyndt, 2017). The nature and meaning of interdependence may be different in work teams compared to learning teams because of the different focus of these teams. The main aim of work teams includes collaborating on and performing one or more tasks. While learning behaviours that may occur in these teams are essential for successful teamwork and task performance, learning is not their sole aim. Conversely, learning teams - such as PLCs - present a framework for organising professional development initiatives in collaboration. The conceptualisation of task and outcome interdependence described below mainly applies to work teams.

Task interdependence can be defined as “the interconnections between tasks such that the performance of one definite piece of work depends on the completion of other definite pieces of work” (Van der Vegt et al., 1998; p. 127). It emanates from the tasks in the team referring to the extent to which interaction, coordination, and collective action of team members are needed to complete tasks and members must rely on their fellow team members to perform their tasks effectively (Guzzo and Shea, 1992; Saavedra, Earley, & Van Dyne, 1993; Van der Vegt, Emans, & Van de Vliert, 1999; Wageman, 1995). Thus in highly entitative teams, members strongly feel that they need each other to perform their own tasks and that communication and coordination are needed to realise the team task.

Van der Vegt et al. (1998) describe outcome interdependence as “the extent to which team members believe that their personal benefits and costs depend on successful goal attainment by other team members” (p. 130). It derives from “the degree to which significant consequences of the work – such as goal attainments and tangible rewards – are contingent on collective performance” (Wageman, 1995, p.146). Hence, outcome interdependence is high when all members profit from the outstanding performance of fellow team members (Van der Vegt et al., 1998). In essence, it refers to the degree to which the team is characterised by team or individual reward structures (whether individual outcomes depend on joint or personal performance) (Beersma, Homan, Van Kleef, & De Dreu, 2013). In short, outcome interdependence refers to the degree to which team members perceive that how well other team members perform has a positive influence on them and the degree to which the team is characterised by team reward structures.

3.2.4 Individual perceptions versus convergence

As suggested above, our conceptualisation of team entitativity is focused on individual team members’ perceptions of dynamic team properties that are mostly not objectively observable but rise from subjective experiences and perceptions. This entails that individual members’ perceptions of their teams’ degree of entitativity may differ. As the focus here is on perceptions of a team level construct, one can wonder what it means for the team when members have a different perception of their team’s degree of team entitativity. The question is whether a collection of individuals can be described as highly entitative when members’ perceptions vary. When individuals’ perceptions vary, the average perception of all members may not be a good representation of a group’s degree of team entitativity. Averaging out individual members’ perceptions ignores the existence of individual variability. Hence, we propose the degree of convergence or agreement on team entitativity within the group, the extent to which there is a shared perception, to also indicate a team’s degree of team entitativity.

This is in line with the fact that the development of a shared vision was put forward as an important characteristic of teams (Salas et al., 2000). Thus, it can be assumed that members of a highly entitative team, strongly meeting such team characteristics, develop a shared vision on their team’s degree of entitativity. Kozlowski and Chao (2012) and Kozlowski (2015) discuss how such sharedness comes to exist and how team-level phenomena and concepts (such as team entitativity) emerge. They argue that different forms of emergence can take place. The composition forms, based on convergent dynamics, are especially applicable here. Translated to the concept of team entitativity, it suggests that as individuals interact in their team, their perception of team entitativity becomes more and more homogeneous and converges. Hence the extent to which individual team members’ perceptions of entitativity (of the defining features) are shared, may also indicate the degree of teamness the team possesses.

A clear operationalisation of entitativity lacks in literature and there is no standard set of items that is used for measurement (Lickel et al., 2000). Moreover, as suggested above, our conceptualisation of team entitativity differs from the traditional entitativity construct. Hence, besides defining team entitativity as a theoretical construct, the present study aimed at developing a measurement instrument based upon the conceptualisation presented above.

As mentioned earlier, the development of this instrument was applied to a specific type of teams-in-practice: teacher teams in secondary education in Flanders (Belgium). More specifically, the focus was on subject groups. These are structural units within the school that gather teachers who teach the same or closely related subjects (i.e., disciplinary teams). They collaborate concerning subject-related matters, such as the curriculum and student evaluation. It was opted to focus on subject groups because they are meaningful collaborative units within each school that are organised to collaborate on core teaching issues (i.e., curricular issues as well as didactical-pedagogical matters). However, the content of their collaboration can vary strongly across groups, some focusing on making superficial practical arrangements, others discussing more profound pedagogical and didactical matters related to the subject.

This study consists of three steps. First, in the questionnaire development phase, an item pool was generated based upon the conceptualisation of team entitativity. Building from this item pool, the measurement instrument was designed and presented to teachers for feedback. Second, in the test phase, this instrument was tested in a large-scale quantitative study. The questionnaire was distributed among teachers in secondary schools in Flanders (in Dutch). In the analyses, two methodological approaches were combined: Classical Test Theory (CTT) to assess the underlying factor structure of the questionnaire and Item Response Theory (IRT) for item-level analyses. Adding IRT analyses to the traditionally performed CTT analyses has several benefits: (a) Besides providing information on how the scale functions, IRT analyses provide detailed information on how the items function; (b) They provide a subject-independent assessment of the items and the scale, resulting in comparable results across groups from the same population; (c) They provide insight in the range of measurement precision of the items and the scale, demonstrating the range of the underlying construct in which the scale is most reliable and thus best at discriminating among individuals. As the IRT techniques used here require unidimensionality of the questionnaire under investigation, the factor structure first needs to be assessed. In a next step, item-level analyses were performed using IRT, providing more detailed information on the item-level and range of effectiveness of the scales. Further analyses were performed to investigate the psychometric quality of the instrument. Finally, the degree to which team members have a shared perception of their team’s degree of team entitativity was investigated. In the third phase, the resulting 15-item instrument was retested to assess longitudinal measurement invariance, test-retest reliability, and predictive validity.

In order to assess the discriminant and predictive validity of the team entitativity instrument, its relationship to two other well-established constructs was investigated. In order to test the discriminant validity of the measure, the distinction between team entitativity and psychological safety was assessed. The latter is often investigated in team research and includes feeling safe to express oneself without fear of damaging one’s self-image, status, or career (Kahn, 1990). In environments that are perceived as psychologically safe, team members are not punished for asking for help or admitting mistakes and are prepared to present new ideas, ask questions, and express concerns because – due to the safe environment – they are not afraid to make a mistake in doing so (Edmondson, 1999; 2008). Similar to team entitativity, it can be described as a belief of the team members about the interpersonal context of the team (Vangrieken et al., 2016). Psychological safety has been demonstrated to be related to positive team processes and outcomes, such as team learning behaviours (e.g., Edmondson, 1999; Van den Bossche et al., 2006; Vangrieken et al., 2016).

Furthermore, in order to test the predictive validity of the measure, the relationship between team entitativity and team work engagement was assessed. Team work engagement (TWE) is “a positive, fulfilling, work-related and shared psychological state characterised by team work vigor, dedication and absorption which emerges from the interaction and shared experiences of the members of a work team” (Torrente, Salanova, Llorens, & Schaufeli, 2012, p. 107). It contains three aspects: vigour, dedication, and absorption. Team vigour is defined as “high levels of energy and an expression of willingness to invest effort in work and persistence in the face of difficulties” (Costa, Passos, & Bakker, 2012, p. 5). Team dedication refers to “a shared strong involvement in work and an expression of a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and challenge while doing so” (Costa et al., 2012, p. 6). Finally, team absorption includes a “shared focused attention on work, whereby team members experience and express difficulties detaching themselves from work” (Costa et al., 2012, p. 6). It is hypothesised that team entitativity may function as a team resource that, based upon the rationale of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) fosters team work engagement. The motivational process included in the JD-R model describes the rise of (team) work engagement as triggered by job resources. These include physical, psychological, social, or organisational job aspects that can help to achieve work goals, reduce job demands, and encourage personal growth and development (Demerouti, et al., 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Team entitativity can be described as such a (team) resource that fosters TWE. This is in line with the model of Albrecht (2012) and Torrente, Salanova, Llorens, and Schaufeli (2012), suggesting that team resources such as team climate and teamwork are positively related to (team) engagement.

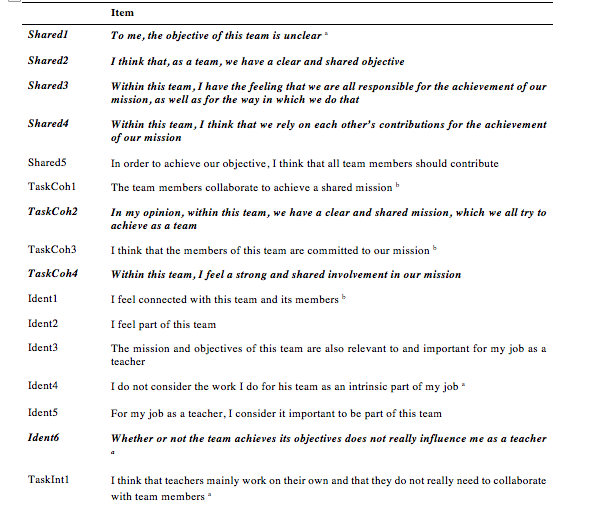

For each of the defining features of team entitativity, literature was searched for existing questionnaires. In this first step, items were collected from a variety of existing (sub)scales (Table 1). From this item pool those items that matched the conceptualisation of one of the defining features were selected and adjusted to fit our conceptualisation. In a next step, additional items were composed to cover those aspects of team entitativity that were not represented in the item pool. This led to the first version of the team entitativity questionnaire including 27 items. Given our research design combining a CTT and IRT approach, two considerations were important in this questionnaire development phase. First of all, in order to be able to select the best functioning items, it is advised to start off with a sufficiently large selection of items. Hence, we started with a broad selection of 27 items, aiming to end up with a more parsimonious instrument with approximately half of the original items. Secondly, based upon the IRT framework it is important to include a broad spectrum of items with varying levels of the construct (i.e., location of the item), referring to the degree of team entitativity you need to have in order to endorse the item. This indicates that items should be situated on different locations of the underlying team entitativity continuum. While some items should only be endorsed by teachers part of highly entitative teams, other items should be easier to endorse in order to distinguish between different teams situated at the lower end of the continuum. When measuring psychological constructs, it is more complicated to judge the levels or location of items compared to when assessing for example math skills (in the latter case the level or location refers to the difficulty of items). Attempting to meet this requirement, (a) a variety of items assessing the same feature were included and (b) where possible some items were formulated more strongly – including more entitativity requirements – than others (e.g., “To me, the objective of this team is unclear” vs. “I think that, as a team, we have a clear and shared objective”; “The team members collaborate to achieve a shared mission” vs. “In my opinion, within this team, we have a clear and shared mission, which we all try to achieve as a team”; “For my job as a teacher, I consider it important to be part of this team” vs. “In order to be a good teacher, I have to collaborate with the other members of my team”).

This version was presented to 42 teachers to evaluate the items. Their remarks, feedback, and suggestions for improvement were used in order to assess whether the items were meaningful for the context of teachers and to further refine the formulation. Overall, all items were perceived as relevant. The teachers made suggestions to reduce the complexity of some items by shortening them and adjusting the terminology. As these were all minor adjustments, the questionnaire remained rather context-independent. The resulting instrument includes five items assessing shared goals and responsibilities, 10 items measuring cohesion (four assessing task cohesion, and six assessing identification), and 12 items aimed to capture interdependence (of which seven measure task interdependence and five outcome interdependence) (see Appendix for a list of the items).

Table 1

Original questionnaires

The instrument was tested in a quantitative study consisting of two waves of data collection among 37 secondary schools in Flanders (a region of Belgium with approximately 6,500,000 inhabitants). In the first wave, 1,677 teachers completed the questionnaire. As one of our aims included the investigation of team members’ shared perception of team entitativity, it is important that a sufficient number of members per team completed the questionnaire. However, as suggested in section 2, teachers are often part of multiple subject teams. In order not to overload these teachers with multiple questionnaires, they were asked to fill out the questionnaire only once (for the team they are most strongly involved with). This choice was made to make sure that the research was practically feasible. The downside of this decision includes that this reduces the potential pool of participants when considering the team level, reducing response rates of some of the teams. Furthermore, being very restrictive regarding the required response rate would probably magnify bias in the sample as it could be hypothesised that more cohesive teams with a higher degree of entitativity have a larger probability of reaching a high response rate. Hence, in order to find a balance between practical feasibility and the need for sufficient variety in team entitativity on the one hand, and the need for a sufficiently high participation rate per team on the other hand, only data of teachers part of the subject teams of which at least 60 per cent (teams with less than 10 members) or 50 per cent (teams with 10 or more members) of the members completed the questionnaire, were retained for analyses. Hence, the data of 1,320 teachers part of 227 subject groups in 35 different schools were used. In the second wave of data collection, 1,178 of the teachers participating in the first wave (70.24%) filled out the questionnaire. The same criteria regarding participation rate per team were used for our second wave, resulting in a sample of 731 teachers (nested in 139 subject groups from 31 different schools) suitable for analyses.

6.1.1 Instrument

The distributed team entitativity measure contained 27 Dutch items. Furthermore, a measure for psychological safety was included to assess discriminant validity. The Dutch version of the seven-item psychological safety instrument of Edmondson (1999) (e.g., Van den Bossche et al., 2006) was used and slightly adapted so the items were formulated from the individual’s point of view (e.g., “I feel that is difficult to ask other team members for help”, instead of “It is difficult to ask other team members for help”). Finally, a measure for team work engagement (TWE) was included in order to assess predictive validity of the team entitativity measure. TWE was assessed with the short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) for teams (Torrente et al., 2012).

Items of the team entitativity and psychological safety questionnaire were answered on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘completely disagree’ to 6=‘completely agree’. TWE was measured using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1=‘never’ to 7=‘always’. Background information was asked about the individual teachers and their team. This included: gender, age, years of teaching experience, information on their appointment, the size of their team, and the number of years they have been part of the team. Regarding teachers’ type of appointment, they were asked to indicate whether or not they are appointed ad interim (i.e., a substitute teacher with a temporary contract) and whether or not they have a permanent appointment in their school.

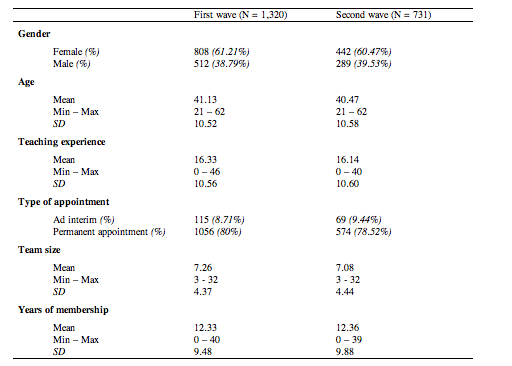

6.1.2 Sample characteristics

Table 2 provides an overview of the sample characteristics. The majority of the respondents indicated to have structurally planned meetings with their team once or a few times per trimester (first wave=83.35%; second wave=84.54%). However, when asked about informal meetings and consultation with colleagues of their team, teachers reported higher frequency levels. Most teachers reported to consult their team colleagues several times a month to several times a week (first wave=65.91%; second wave=67.44%), a substantial part of the teachers even reported daily consultations (first wave=13.33%; second wave=13.41%).

Table 2

Sample characteristics

6.1.3 Analyses

Because the instrument assesses teachers’ perceptions of their team, a first step was investigating the degree of team level variance and associated appropriateness and feasibility of multilevel analyses. This was investigated by means of the intraclass correlation (ICC(1) and ICC(2)) coefficients and design effects of the items. The ICC coefficients assess group reliability. ICC(1) refers to the proportion of the total variance that can be explained by team membership (Newman & Sin, 2009). As stated by Dyer, Hanges, and Hall (2005) multilevel analyses may provide minimal practical benefits and may be difficult or impossible to estimate when ICC(1)s are smaller than .05. ICC(1) values of the items ranged from .010 to .132 (M=.059), 12 items having an ICC(1) value below .05, and design effects were all below 2 (M=1.286, Min = 1.049, Max = 1.636). The ICC(2) coefficients indicate the reliability of the group means (Bartko, 1976; Newman & Sin, 2009). ICC(2) values of the items range from .13 to .53 (M=.35), indicating that aggregate group means are not reliable because of high levels of within-group variance. Given the low ICC(1) and ICC(2) values and design effects, it was opted to perform analyses at the individual level. In order to take the clustering in our data into account, the “type is complex” command was used in the Mplus analyses. While this does not specify a model on two levels (individual and team), it takes the clustering of the data into account when computing standard errors and Chi-square tests of model fit.

Dimensionality. In order to assess the structure of the questionnaire, the sample of the first wave was split in two stratified subsamples, a development sample (n1= 662) and a validation sample (n2=658). Stratification was based upon school on the one hand and team size on the other hand: All schools and team sizes are equally represented in both samples. The development sample was used to investigate the structure of the questionnaire by means of exploratory factor analyses (EFA, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors). Oblique rotation (Direct Oblimin) was used because it was assumed that the different factors are related as they are derived from the same underlying construct. Moreover, as suggested in the conceptualisation of team entitativity, the different features are – based on theory – assumed to be related. Next, the identified structure was assessed in the validation sample by means of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and hierarchical CFA (maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors). Internal consistency was examined using the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. In the analyses, the complex data structure (i.e., clustered) was taken into account, computing robust standard errors and Chi-square statistics.

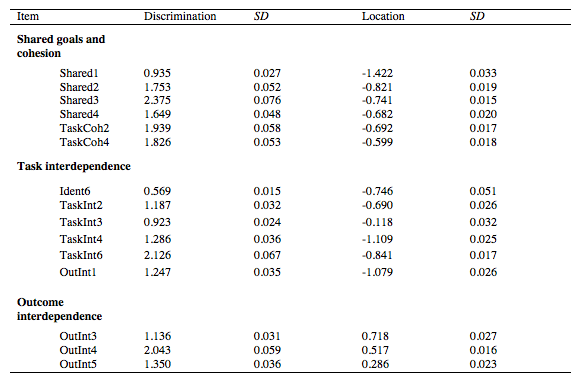

Item-level analyses. Next, the full sample of the first wave (N=1,320) was used in order to assess the performance of the individual items within the derived structure using IRT analyses. A graded response model was used, which estimates two parameters for each item: a discrimination parameter (slope) and a location parameter. These analyses were performed for each factor of the structure derived from EFA and CFA analyses separately.

Final questionnaire. Based upon the combination of the structural analyses and item-level analyses, the final questionnaire was composed and again assessed in the validation subsample of the first wave (n2=658) using CFA and internal consistency analyses. Moreover, shared variance of the items within each factor and discriminant validity of the factors were assessed in line with the guidelines of Fornell and Larcker (1981). Furthermore, in order to investigate the degree to which team members have a shared perception of their team’s degree of team entitativity, within-group agreement (Rwg) scores were investigated (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984). Finally, based upon the retest of the questionnaire, longitudinal measurement invariance and predictive validity of the questionnaire were assessed.

The calculation of the inter-item correlations, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity to check the suitability of our data for EFA, was done in SPSS version 23. Factor analyses and analyses investigating longitudinal measurement invariance and validity (discriminant and predictive) were performed in Mplus version 7.4 using “type is complex” to take nesting of our data into account. The Satorra-Bentler correction was used when comparing the different models assessing longitudinal measurement invariance (Satorra & Bentler, 2010). IRT analyses were performed using PARSCALE. All other analyses were performed in R version 3.2.1 (R Core Team, 2015) using the package psych (Revelle, 2012).

7.1.1 Exploring the structure

First, inter-item correlations were assessed in the development sample (first wave) to detect redundant items that do not increase construct coverage of the scale. Of each item pair demonstrating a correlation above .75, one item was omitted. Both items of each of these sets of items were situated in the same defining feature of team entitativity. Hence, all features remained sufficiently represented. The selection of these items was based upon conceptual reasons as the retained items more clearly covered the intended content. Next, it was assessed whether our data were suitable for EFA. Sample size was sufficiently large (n= 662), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy equalled .920 and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (Χ2=7823.62, df=253, p<.001). This indicates that the inter-correlation matrix contains enough common variance to make EFA useful.

EFA were performed on the development sample (n=662) in order to investigate the structure of the questionnaire. Based upon the eigenvalues (i.e., larger than one), the scree plot, and conceptual reasons, a three-factor solution proved to be most valid. Moreover, all items that were included had to have a loading larger than .40 on one of the factors and were not allowed to have high cross-loadings. The latter means that items had to have relatively low loadings on other factors (below .30) and that the difference between an item’s loading on one factor and its loading on another factor was not allowed to be below .20. Eight items not meeting these criteria were omitted. The resulting factor solution is presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Results exploratory factor analysis (oblique rotation)

The first factor includes seven items referring to shared goals and responsibilities, and cohesion (task cohesion and identification) and is labelled shared goals and cohesion. The items intended to measure the importance of the team to its members (theoretically assumed to be part of the cohesion feature), are not represented in this solution. The second factor includes five items primarily referring to task interdependence. Although this factor includes one item (OutInt1 in the Appendix) originally intended to assess another defining feature - outcome interdependence - evaluation of its content demonstrated it to be closely related to task interdependence. The final factor includes three items referring to outcome interdependence.

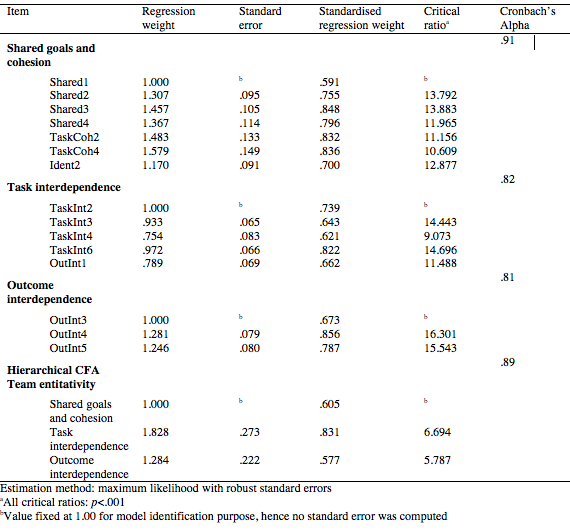

7.1.2 Confirming the structure

The structure derived from EFA was assessed in the validation sample (n=658) (first wave) by means of CFA. The ratio of sample size to number of items exceeded the ratio of 10:1, indicating that our data were suitable for CFA (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham, 2006). Furthermore, the ratio of sample size to number of free parameters to be estimated in the model exceeded the required minimum of 10:1 (Bentler & Chou, 1987). CFA resulted in a good fit of the assumed model (Χ2/df =2.85; df=87; CFI=.952; TLI=.942; RMSEA=.053 [90 % CI [.045; .061]]; SRMR=.044) since these fit indices met the generally accepted norms for CFA (Brown & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Table 4 presents an overview of the resulting CFA solution.

Table 4

Results (hierarchical) confirmatory factor analysis

To test the assumption that all three factors are indicators of the same underlying construct, a hierarchical CFA was performed. In this model, the same factor model as included in the regular CFA was tested with an additional latent factor encompassing the three other factors. Again, fit indices confirmed an appropriate fit of the presumed factor model (Χ2/df=2.85, df=87; CFI=.952; TLI=.942; RMSEA=.053 [90 % CI [.045; .061]]; SRMR=.044). Results can be found in Table 4.

7.1.3 Internal consistency

All Cronbach’s α values were sufficient and did not significantly increase if one of the items would be dropped (Table 4). Moreover, item-whole correlations were assessed to investigate whether the included items correlated sufficiently with the scale as a whole. It was opted to assess corrected item-whole correlations as these correct for item overlap and scale reliability (Revelle, 2012). For shared goals and cohesion corrected item-whole correlations ranged from .61 to .84. For task interdependence these scores ranged from .62 to .81 and for outcome interdependence from .66 to .81. Moreover, for the hierarchical team entitativity factor corrected item-whole correlations ranged from .42 to .75.

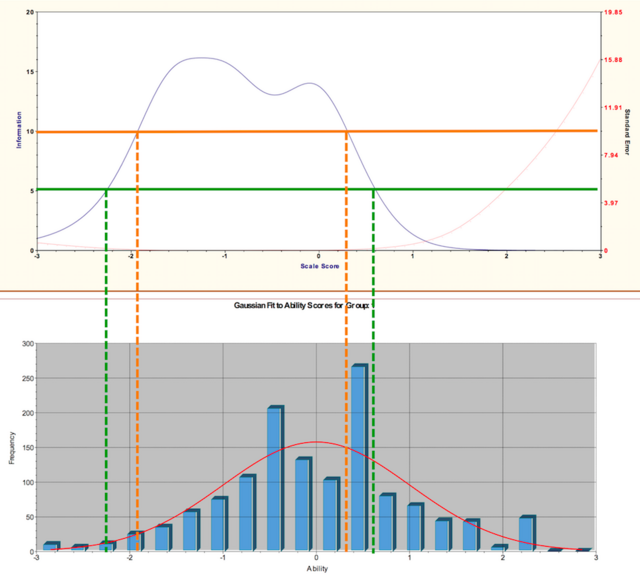

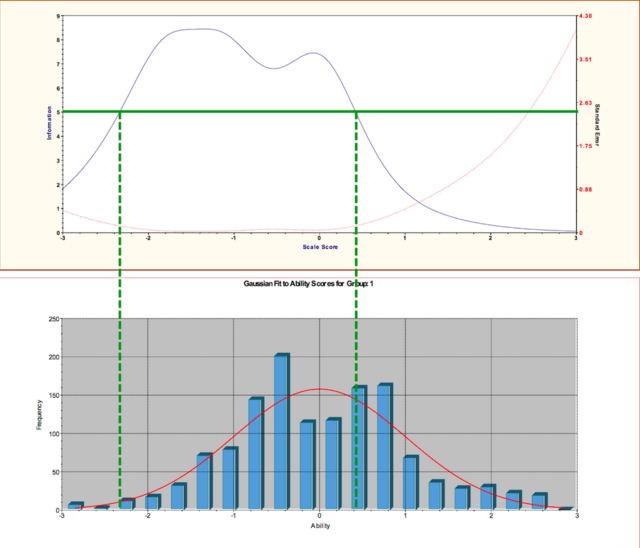

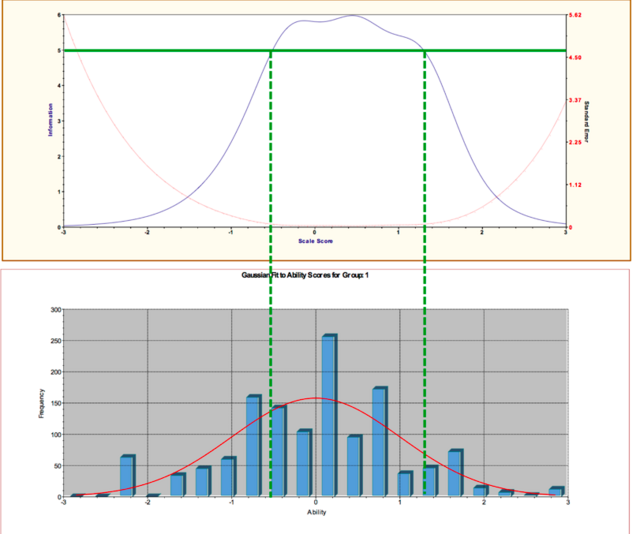

The next step of our analyses included the application of IRT analyses to assess the performance of the items included in the questionnaire. A two-parameter logistic model was used. The location parameter indicates the level of the construct: the larger the location of an item, the more of the measured construct a respondent must have in order to endorse the item (Edelen & Reeve, 2007). Items with a different location provide information at different points of the underlying construct or trait (i.e., shared goals and cohesion; task interdependence; outcome interdependence). While items with a low location parameter are best at discriminating among people at lower trait levels, items with a high location parameter can best discriminate at higher trait levels (Reise, Ainsworth, & Haviland, 2005). The mean of the location parameter is set to zero. The discrimination parameter refers to the extent to which the item is related to the underlying construct and how good the item is in discriminating among different individuals (at the level of the location parameter) (Edelen & Reeve, 2007; Reise et al., 2005). As unidimensionality is a prerequisite to perform these analyses, IRT analyses were performed for each factor separately. For each factor, following results will be discussed: (a) the test information curve (TIC), demonstrating the degree of reliability or measurement precision of the scale at different levels of the underlying measured construct; (b) estimates of the parameters; and (c) the item-characteristic curves, demonstrating the relationship between someone’s response to an item and his or her level of the underlying measured construct.

The TIC (figures 1, 3, and 5) demonstrates the psychometric information of the test (i.e., its ability to differentiate among individuals) at each level of the underlying construct. This indicates the instrument’s measurement precision or how well it functions at the different trait levels. Accordingly, the standard error of measurement (red curve in the graph) is inversely related to the TIC: The higher the information level of the TIC, the lower the standard error. The psychometric information provided by the test is thus analogous to test reliability in CTT. However, while in the latter case reliability is the same for all individuals, in IRT analysis this can vary depending on the position of the individual on the trait continuum (Reise et al., 2005). In the results presented below, the TIC for each factor is shown together with the distribution of the underlying trait in the sample. The latter (a histogram) indicates how many people in each area of the construct are present in the sample. Two aspects - analogous to the two parameters (location and discrimination) – are important when interpreting the TICs. First of all, the location of the curve along the continuum of the underlying construct indicates in what areas of the scale the instrument provides most information. Secondly, the height of the curve demonstrates how much information the test provides for the different trait levels. An information level of five (y-axis in the graph presenting the TIC) corresponds to a reliability of .80 (blue line in the figures); a level of 10 indicates a reliability of .90 (orange line). The area in which these reliability levels are reached are indicated with dotted vertical lines (respectively blue or orange) in the distribution histograms. This indicates the range of people for whom the scale is reliable at a level of .80 or .90.

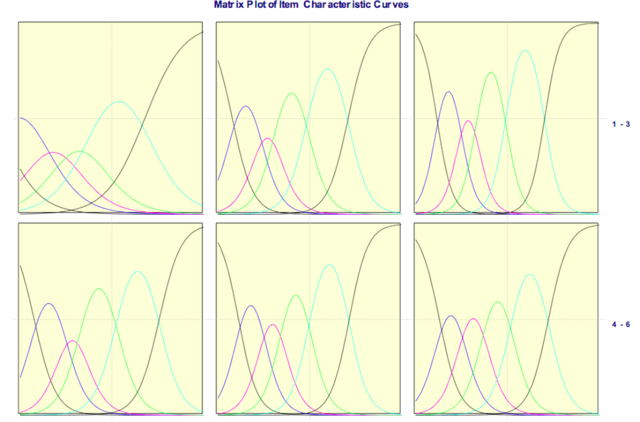

The item-characteristic curve describes the relationship between an individual’s position on the continuum of the measured latent construct (i.e., shared goals and cohesion; task interdependence; outcome interdependence) and the probability that he or she will indicate a particular response for an item that is aimed to measure that construct (Reise et al., 2005). In polytomous response models (used here), the graphs for each item include a curve for each response category. The matrix plots (Figure 2, 4, and 6) show the item-characteristic curves of the items included in each respective factor. As indicated, each curve represents one of the response categories (1 to 6). The difference in discrimination is demonstrated in the steepness of the curves for each response category and the degree to which these curves are distinguished rather than overlapping. The location of the items is demonstrated in the position of the curves on the horizontal axis (continuum of the underlying construct), items with curves mostly situated on the left side are easier to endorse compared to items on the right side.

7.2.1 Shared goals and cohesion

One non-functioning item had to be omitted from the factor shared goals and cohesion in order for the scale to function appropriately (Ident2). The response categories of this item violated the assumption of ordinality. The TIC of this scale (Figure 1) demonstrates that the scale is most reliable at the lower and middle range of the underlying trait.

Figure 1. TIC and distribution underlying trait shared goals and cohesion.

A reliability of .90 (i.e., 10 on the information axis) is reached between trait levels -2 and approximately 0.20 and a reliability of .80 (i.e., 5 on the information axis) is reached between approximately -2.30 and 0.60. When interpreting this range it is important to compare this to the distribution of the underlying trait (Figure 1), indicating that a large part of the sample can be assessed reliably using this scale. This is reflected in the slope (discrimination) and location parameters (Table 5).

Table 5

IRT parameter values

The range of the location parameters demonstrates that most of the item response categories are endorsed by respondents with lower than average shared goals and cohesion. This confirms that the scale is most useful in discriminating among individuals at the lower end of the trait continuum. The item parameters described above are visually presented in the item characteristic curves in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Matrix plot item characteristic curves shared goals and cohesion.

7.2.2 Task interdependence

Compared to the structural analyses, IRT analyses of this factor indicated that one item should be retained in order for this scale to function well (Ident6). Without this item, IRT analyses did not run correctly and the other items did not function appropriately. This item was selected to be included because of conceptual reasons: The content matches with the other items in the factor and is an added value to the overall content of the factor. The TIC of task interdependence (Figure 3) demonstrates that a reliability of .80 is reached between a trait level of approximately -2.40 and 0.40. The bottom half of Figure 3 indicates which part of the sample can be assessed with this level of reliability.

Figure 3. TIC and distribution underlying trait task interdependence.

The parameter values (Table 5) again confirm that this scale provides most information and thus is most reliable in the lower and middle range of the trait. The item-characteristic curves for the task interdependence items are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Matrix plot item characteristic curves task interdependence.

7.2.3 Outcome interdependence

The TIC of outcome interdependence presented in Figure 5 demonstrates that a reliability of .80 is reached between trait levels of approximately of -0.50 and 1.30. The bottom half of Figure 5 again indicates which part of the sample can be assessed with this level of reliability.

Figure 5. TIC and distribution underlying trait outcome interdependence.

Hence, compared to the TICs of the previous factors, this scale provides most information at higher ends of the trait continuum. This is confirmed by the parameter values (Table 5). Figure 6 shows the item-characteristic curves for the outcome interdependence items.

Figure 6. Matrix plot item characteristic curves outcome interdependence.

The solution found appropriate in the IRT analyses was retested using the principles of CTT. This means that item Ident2 was omitted from the first factor and Ident6 was included in factor two. For these analyses the validation sample of the first wave (n2 = 658) was used.

7.3.1 CFA and internal consistency

The results in Table 6 demonstrate that the combined solution resulted in a good fit of the assumed model with our data. Results of the hierarchical CFA indicated an appropriate fit (Χ2/df=3.07; df=87; CFI=.945; TLI= .934; RMSEA=.056 [90 % CI [.048; .064]]; SRMR=.050). All Cronbach’s α indicators (Table 6) were sufficient. For shared goals and cohesion, corrected item-whole correlations ranged from .58 to .85. For task interdependence these scores ranged from .46 to .80 and for the outcome interdependence factor from .66 to .81. Moreover, for the hierarchical team entitativity factor corrected item-whole correlations ranged from .43 to .73.

Table 6

Results (hierarchical) confirmatory factor analysis combined solution

7.3.2 Shared variance and discriminant validity

In order to investigate the shared variance of the items within the latent variables of the model, the squared multiple correlations (R2) of the items were assessed. For shared goals and cohesion, these ranged from .331 to .728, with a mean of .609, indicating that the six items in this scale account for 60.9% of the variance in these items. For task interdependence, 44.53% of the variance in the items is accounted for in this factor (range of R2 from .232 to .653). Finally, for outcome interdependence the three items in this scale account for 60.18% of the variance in these items (range of R2 from .452 to .733).

To assess discriminant validity, the guidelines of Fornell and Larcker (1981) were followed. They state that the average variance extracted by the latent factor should be higher than the variance explained by the correlation with another factor. Discriminant validity is proven when the root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeds the inter-factor correlations. The square root of the AVE exceeded the correlation between each respective factor and other latent factors (Table 7). Next, discriminant validity was assessed in relation to psychological safety. CFA (again controlling for the clustering in the data) indicated an acceptable fit of the psychological safety instrument with our data after allowing covariance between one pair of items (Χ2/df=4.31, CFI=.944; TLI=.909; RMSEA =.071 [90 % CI [.053; .091]]; SRMR=.045). The standardised Cronbach’s α coefficient equalled .84. The square root AVE for each team entitativity factor exceeded the correlation between psychological safety and both the subscales as well as hierarchical scale of team entitativity (Table 7), supporting discriminant validity of the instrument. However, the high correlation between shared goals and cohesion, and psychological safety indicates that both constructs are strongly related. Experiencing your team as cohesive around shared goals and tasks appears to be strongly related to experiencing psychological safety in your team. This indicates the need for caution when investigating the role of these concepts in predicting other team processes or outcomes.

Table 7

Correlation between team entitativity and psychological safety

7.3.3 Convergence of team members’ perceptions

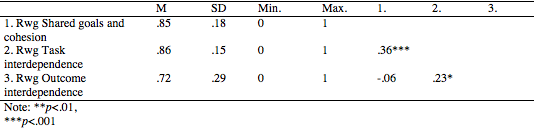

As suggested earlier, our conceptualisation and operationalisation of team entitativity focuses on the individual team members’ perception of their team. This assumes that individuals’ responses within a team may vary, which was confirmed by the low ICC(1) and ICC(2) values and design effects. The extent to which these perceptions vary can also be seen as an indicator of the team’s degree of team entitativity. Teams are supposed to develop a shared vision, inter alia on their own functioning (Salas et al., 2000). The degree to which such a shared vision is present was investigated using the indicator for within-group agreement Rwg proposed by James, Demaree, and Wolf (1984). Rwg ranges from zero (complete absence of agreement) to 1 (full agreement). Given the existing variety in individual team members’ perceptions of team entitativity, it is valuable to assess within-group agreement rather than calculating the average degree of entitativity of a team. Aggregating individuals’ perceptions of their team’s degree of team entitativity, as is often done in research on team constructs, would not do justice to the complexity of team phenomena such as team entitativity. This neglects the individual-level variance, which was demonstrated to be substantial in this sample (see below). Within-group agreement of each team was calculated for each factor, descriptive statistics are shown in Table 8. In this case agreement on outcome interdependence appears to be the lowest and has most variation.

Table 8

Descriptive statistics and correlations within-group agreement

Moreover, the degree of variance on both the within and the between level was investigated. Results demonstrated that most of the variation appeared to be situated on the individual level. The within-level variances equated to .79, .63, and 1.24 while the between-level variances are .087, .051, and .055 for respectively shared goals and cohesion, task interdependence, and outcome interdependence. Hence, most of the variance in the sample can be attributed to individual-level differences within teams while relatively little variance can be explained by the clustering in different teams.

Combining the insights derived from the Rwg scores and distribution of variance across the within and between level, a more nuanced perspective on convergence of perceptions can be put forward. While moderate to relatively high Rwg scores indicate that team members’ perceptions of team entitativity are quite similar within teams (members tend to converge to some extent), analysing the variance components demonstrates that team-level variance is low. Hence, most of the differences in scores can still be attributed to differences between individuals rather than differences between teams. This is also demonstrated in the broad range of Rwg scores (ranging from complete disagreement to complete agreement). This range indicates that in a substantial amount of teams, members’ perceptions of team entitativity tend to diverge and are very different. This indicates the value of also investigating team entitativity as a construct varying at the individual level – as most of the variance was situated on this level – with within-group agreement as a team-level indicator of convergence of entitativity rather than using it to assess an arbitrary cut-off argument for aggregation.

7.4.1 Dropout analyses

ANOVA analyses were used to assess whether the mean team entitativity scores of teachers who were included in the second wave (n=731) differed significantly from those not included in the retest (n=589). Teachers who did not participate in the second wave, scored slightly lower on shared goals and cohesion (F=14.05, df=1318, p>.01, η2=.01) and task interdependence (F=4.06, df=1318, p<.05, η2<.01) in the first wave. However, the low effect sizes indicate an overall limited effect of attrition on the results. No significant differences were found for outcome interdependence (F=.66; df=1318; p=.42, η2<.001).

7.4.2 Internal consistency retest

All Cronbach’s α values were sufficient and did not significantly increase if one of the items would be dropped. For shared goals and cohesion (α=.90), corrected item-whole correlations ranged from .56 to .88. For task interdependence (α=.82) these scores ranged from .40 to .80 and for outcome interdependence (α=.83) from .76 to .78. Moreover, for the hierarchical factor (α=.89) values ranged from .37 to .73.

7.4.3 Longitudinal measurement invariance

Next, it was investigated whether the measurement of team entitativity is equivalent over time, meaning that the same construct with the same structure is measured. For each factor it was tested whether factor loadings and intercepts are equal over time (Coertjens, Donche, De Maeyer, Vanthournout, & Van Petegem, 2012). This was done by means of testing and comparing three models: (1) a baseline model (i.e., the basic model structure is invariant, factor loadings can differ over time), (2) a model including invariant loadings over time (i.e., metric invariance, items are interpreted in a similar way), and (3) a model including invariant intercepts over time (i.e., scalar invariance). The results (Table 9) indicate that for shared goals and cohesion, factor loadings and intercepts were invariant. For task interdependence, loadings can be assumed invariant over time (ΔΧ2=4.41, Δdf=5, p=.492). The Chi-square difference test for investigating invariance of intercepts was significant (ΔΧ2=19.49, Δdf=5, p=.002). Because this test is influenced by the large sample size, the difference in CFI was checked, confirming intercept invariance (ΔCFI=.006). For outcome interdependence, the assumption of invariant loadings was again confirmed (ΔΧ2=1.10, Δdf=2, p=.576). However, only partial intercept invariance was reached. Assessment of the items demonstrated that mostly OutInt3 violated the assumptions. When estimating a partial intercept invariance model (freeing the constraint on the intercept of OutInt3) an improved model fit was found. The difference in CFI (ΔCFI=.003) confirmed partial intercept invariance. This indicates caution when using sum scores of outcome interdependence when making comparisons over time.

Table 9

Longitudinal measurement invariance

7.4.4 Test-retest reliability

Correlations between the first and second wave equalled .69 (p<.001) for shared goals and cohesion, .62 (p<.001) for task interdependence, and .53 (p<.001) for outcome interdependence. As stated by Kyndt et al. (2014), these moderate values can indicate that the underlying constructs in themselves are not stable over time. This is in line with the conceptualisation of team entitativity as a dynamic construct. Moreover, test-retest reliability assumes that the whole group of participants changes in the same way over time and does not take individual differences in these evolutions into account. However, the focus of our conceptualisation on an insider perspective - looking at individuals’ perceptions - and high levels of individual-level variance (demonstrated in low ICC(1), ICC(2), and design effects), indicate extensive individual differences.

7.4.5 Predictive validity

In order to check predictive validity, it was assessed whether the different aspects of team entitativity (first wave) are related to TWE (second wave). CFA (taking the clustering in our data into account) indicated an appropriate fit of the TWE instrument with our data (Χ2/df=3.00; df=23; CFI=.987; TLI= .981; RMSEA=.055 [90 % CI [.041; .070]]; SRMR=.017). All team entitativity features were significantly correlated to the TWE components (Table 10). With regard to the within group agreement variables, a small positive significant correlation was found between agreement concerning shared goals and cohesion and task interdependence on the one hand and dedication on the other hand and a small negative correlation between agreement concerning outcome interdependence and absorption.

Hence, in line with the theoretical assumptions of the Job-Demands Resources model, the three defining features of team entitativity were positively related to TWE measured at a later point in time. The relationship was strongest for shared goals and cohesion. This confirms predictive validity of the scales. However, less compelling results were found regarding within-group agreement; the latter does not demonstrate strong predictive validity in relation to TWE in this sample.

Table 10

Correlation between team entitativity and team work engagement

Team entitativity was introduced here in order to tackle the conceptual gap between real teams and other types of groupings or pseudo-teams. The latter tend to be prominent in the educational sector as teacher teams are often teams-in-name only, leaving them neglected in traditional team research. The team entitativity concept tackles this gap by proposing a continuum-based conception of teams, referring to the degree to which a collection of individuals possesses the quality of a team and thus meets the criteria included in team definitions. In this way, it transcends the black-and-white conception in team research, opening up team research to various team types that were previously excluded. To determine the degree of team entitativity, three defining features were described based upon a combination of traditional team definitions and research on entitativity. These features include: shared goals and responsibilities, cohesion (task cohesion and identification with the team), and interdependence (task and outcome interdependence).