Frontline Learning Research Vol.4 No.4 Special

Issue (2016) 7 - 19

ISSN 2295-3159

aUniversity of Haifa, Israel

bThe Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Article received 18 September / revised 25 January / accepted 16 March / available online 11 May

This theoretical paper is about the role of emotions in historical reasoning in the context of classroom discussions. Peer deliberations around texts have become important practices in history education according to progressive pedagogies. However, in the context of issues involving emotions, such approaches may result in an obstacle for historical clairvoyance. The expression of strong emotions may bias the use of sources, compromise historical reasoning, and impede argumentative dialogue. Coping with emotions in the history classrooms is a new challenge in history education. In this paper, we suggest that rather than attempting to foster positive emotion only or to avoid emotions all together, we should look at ways of engaging with emotion in history teaching. We present examples of peer deliberations on charged historical topics according to three pedagogical approaches that address emotions in different ways. The protocols we present open numerous questions: (a) whether facilitating engagement with own and the other's emotions may lead to better processing of information and better deliberation of a historical question; (b) whether promoting national pride boosts reliance on collective narratives; and (c) whether adopting a critical teaching approach eliminates emotions and biases. Based on these examples and findings in social psychology, we bring forward working hypotheses according to which we suggest that instead of dodging emotional issues, teachers should harness emotions – not only positive but also negative ones, to critical and productive engagement in classroom activities.

Keywords: teacher identity; knowledge building; inquiry learning; problem-centered pedagogy; technology

Emotions are responses to internal or external events with particular significance for the organism. They include verbal, physiological, behavioral, and neural mechanisms (Fox, 2008). Emotional experience involves the coordination and synchronization of bodily symptoms, action tendencies, and feelings, driven by appraisal processes (Scherer, 2005). Although the inclusion of cognitive appraisal (the evaluation of events and objects) in emotions is controversial, cognition is considered either as part of the emotion experience or as interacting with emotion. In his celebrated book, Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, neurologist António Damásio (1994) explains that emotions guide (or bias) behavior and posits that rationality requires emotional input. He argues that René Descartes' "error" was the dualist separation of mind and body, rationality and emotion. Researchers from other domains express comparable claims: For biologists Maturana and Varela (1987), cognition, language and mood or emotion are inextricable. For semiotician Radford (2015), all emotions and motivations are inherently social and culturally constructed, and do not necessarily obstruct thinking.

The question for the educationalist is then how to handle emotions when aiming to foster rational reasoning. This issue is particularly challenging in historical reasoning: since psychologists showed that strong emotions and loyalties hinder rational thinking in general (Bless & Fiedler, 2006), some researchers in History education suggest avoiding strong and negative emotions holding a sway over cognition (Foster, 2013). Moreover, politicians and decision makers are often adamant to avoid negative emotions in history classes for ideological reasons (Evans, Avery, & Pederson, 1999). In other words, although research has shown the intricate relations between rationality and emotion, many opt lessening bursts of strong emotions in history classes. Descartes comes in again through the backdoor.

In the present paper, we claim that handling and capitalizing on emotions as resources for learning is a major goal in history education in the 21st century. We focus on face-to-face deliberative argumentation about highly loaded historical issues, a context that exacerbates emotions in the case of History (Schwarz & Goldberg, 2013) and fosters reasoning and learning in general (Schwarz & Asterhan, 2010). We provide examples of teaching approaches designed to engage emotions in different ways and exemplify how these emotions affect deliberative discussions of historical topics in productive or counter-productive directions. We rely on these examples to articulate hypotheses on the beneficial and detrimental roles of emotions in deliberative historical argumentation.

Historical research has long strove for impartiality, and even when presumptuous aspirations for objectivity were abandoned, emotionality and partisanship are still considered hindrances (Haskell, 1990). School history teaching, while attuned to various other goals besides promoting norms of academic historical practice, is also shifting to a growing extent to emphasizing rational disciplinary thinking and discourse (Barton, 2009; National Center for History in the Schools, 2010). In a survey of leading history education experts, only one of the ten intellectually challenging core practices of history teaching they recommend refers (tangentially) to learner emotions ("connect to personal/cultural experience"). Even then, the emphasis is on helping learners properly distance themselves from personal reaction and views (Fogo, 2014). Some educationalists are even more explicit: Foster's (2013) review of teaching controversial issues advises eschewing the highly emotive topics in favor of more distant events, in order to allow learners to better focus on disciplinary practices. Accordingly, the majority of teachers tend to avoid charged and emotive issues in history teaching (Levstik, 2000). Issues arousing strong (negative) emotions are often considered "taboo" and are formally or covertly sanctioned (Evans et al., 1999). Evasion is more frequent with topics that shed unpleasant light on learners' in-group, and may elicit collective shame or guilt which are aversive emotions (Helmsing, 2014; Wohl, Branscombe, & Klar, 2006). Indeed, historical issues bearing on identity are especially emotion intensive and the emotions they may raise are nor solely positive (McCully, 2006).

Zembylas and Kambani (2012) claim the emotional risk and complexity of teaching controversial historical issues are especially threatening in societies divided by intergroup conflicts. Such a risk arises due to history's role in learners' identity formation, constructing a meta-narrative in which learners position themselves (Goldberg, Porat, & Schwarz, 2006). This may be the reason curriculum policy makers tend to restrict learners' encounter with out-group historical narratives (Bar-Tal, 2007; Goldberg & Gerwin, 2013; Hilton & Liu, 2008). Even educational initiatives designed to engage students with their nation's multicultural history such as Euroclio's initiatives for the new Post Soviet democracies, have been criticized for a tendency towards harmonization and towards the evasion from conflictual episodes (Maier, 2011).

History education experts claim learners should check personal inclinations and emotions lest they be prone to bias and "presentism" (Davis, Yeager, & Foster, 2001; Wineburg, Mosborg, & Porat, 2001). In the context of emotionally charged topics that are more salient in collective memory learners' evidence evaluation tended to be more biased (Goldberg, Schwarz, & Porat, 2008). When confronted with accounts of their nation's history that posed threat to their national pride, patriots demonstrated biased processing of historical information (Miron, Branscombe, & Biernat, 2010). Thus, emotions and issues arousing strong emotions seem to threaten “good” rational and disciplinary oriented learning. However, can identity and emotions be side tracked without losing essential aspects of history teaching?

Some educationalists harness emotions to history learning. For example, Zembylas and Kambani (2012) call for a focus on the emotional side of teaching (contested) history, to purposefully engage learners with discomforting emotions in reference to sensitive historical topics. For them, empathizing is a strategy to be practiced (Zembylas, 2004; Zembylas, 2013). Britzman (2000) refers to the importance of engaging with learners' emotions when teaching about historical collective trauma. None of the above researchers is interested in history teaching as an end in itself, though. Their educational aim concerns reconciliation between adversaries. In the Learning Sciences, there is now a general recognition of the importance of relating curriculum to learners' identity and community history and of engaging them in advocacy and social critique to boost motivation for learning (Thompson, 2014; Varelas, 2012). Barton and McCully (2010) stress that encountering conflicting historical perspectives through critical disciplinary inquiry may help students engage in an internally persuasive dialog about the past and achieve a tolerant and receptive identity. Instead of dodging the role of emotions and of identity, Gottlieb, Wineburg, and Zakai (2005) claim one should acknowledge identity influences on historical understanding, and accept the fact that individuals apply different critical standards to historical sources central and peripheral to group identity. Muller Mirza and colleagues (Muller Mirza et al., 2014) point to the importance of "secondarisation" of emotion, the process in which individuals reflect on their emotions and generalize them into more abstract concepts. Such a process is essential for handling contentious intercultural topics and for academic achievement. Bar-On and Adwan (2006) advocate structuring history teaching to help learners acknowledge their own and the other's emotions and collective identity. They assume this would help deliberating contentious issues of the past in a more productive and reasoned way and motivate engagement with it. However, the effects of affirmation of sentiments relating to national identification and collective narrative have not been explored so far.

We present here a study enabling a comparison between three approaches to history learning – disciplinary critical inquiry, mutual narrative acknowledgement and patriotic apologetic teaching, and by such we inquire about relation between emotion and learning in history. To do so, we focus on inter-group deliberative discussions (or deliberative argumentation) on a "hot" historical topic: Deliberative argumentation is a propitious context for learning (Schwarz & Asterhan, 2010); hot historical topics are lieux de memoire where identity and national identification (or national pride) are susceptible to emerge. Our working hypothesis is that emotion and identity do not constitute obstacles to deliberative discussions or disciplinary practice by themselves. To check our hypothesis, we compare examples of peer deliberations with different structuring of engagement with emotions. In the last part of the paper, we rely on these examples to articulate hypotheses on the role of emotions in deliberative argumentation.

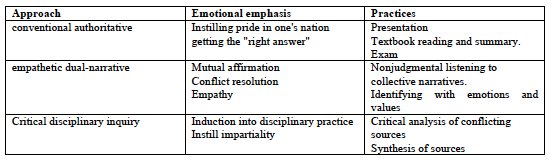

Learners' emotions were addressed through three approaches to history teaching (for full details see Goldberg and Ron's (2014) description of procedure). The first is an authoritative single-narrative approach aligns with declared national history teaching goals such as acquiring factual knowledge of main events and enhancing students' commitment to the state and their collective identity (Israeli Ministry of Education, 2015). Instruction according to this approach was based on a textbook chapter written under direct governmental supervision to produce a clear account stressing the righteousness of Israel (Domke, Urbach, & Goldberg, 2009; Yaron, 2009). Teaching was an "initiation-recitation-evaluation" session with a Powerpoint presentation, directed at getting the "right answer" in a short quiz and instilling pride in one's nation. This conventional lower order thinking type of teaching appears to be very common in social studies classrooms (Saye & Social Studies Inquiry Research Collaborative (SSIRC), 2013) and aligns with Helmsing's examples of reasoning that does not challenge national pride (2014).

The second approach is empathetic dual-narrative. It aims at arousing feelings of empathy for the other and mutual affirmation of collective sentiments. Instruction was based on excerpts from a dual narrative history textbook created by Jewish and Palestinian teachers (Adwan & Bar-On, 2004; Bar-On & Adwan, 2006). Learners were driven to empathetic attention to the emotions and values of adversary narrators and reflection on the reactions they arouse. This practice aligns to some degree with the process of secondarisation, in which learners reflect on emotions and produce more generalized understanding of their social aspect (Mirza, Grossen, de Diesbach-Dolder, & Nicollin, 2014).

Finally, the critical inquiry approach aims at modelling disciplinary practice and developing critical thinking skills (Reisman, 2012). Instruction was based on the use of conflicting sources accompanied with information allowing inferences as to context, goal and bias of authors. Teachers coached students in sourcing and corroboration (Wineburg, 2001) and explicitly attempted to instil impartiality in the encounter with evidence (instructing them to read like a "Swedish" [i.e. neutral] historian). Table 1 succinctly summarizes the emotional emphases and practices of the three approaches.

Jewish and Arab Israeli students from diverse schools were randomly allocated to study the topic of the 1948 war ("war of independence") in one of the three approaches. Two weeks later, participants were paired by teaching approach into Jewish-Arab dyads; they engaged in deliberative discussion of the war and the causes of the Palestinian refugee problem, a topic bound to raise emotional reactions. All discussions were audiotaped and transcribed.

We marked all discussion episodes that included direct references to history or identity, or use of historical disciplinary practices (sourcing, contextualization, perspective taking, causal explanation) (Lee & Ashby, 2000; Wineburg, 2001). Two researchers coded ten of the sixty discussion, and arrived at 75% agreement. Differences were discussed and resolved. The rest of discussions were analyzed separately. We bring forth four episodes we deem representative of potential effects of teaching approaches on the relations of emotion and learning in history.

Table 1

Teaching approaches, emotional emphases and practices

Figure 1 shows a first protocol in the critical-inquiry condition. At the beginning of the discussion (not presented here), the Jewish participant devoted almost four times as many words to analysis and evaluation of the sources as his Arab peer (416 vs. 111 words). Could this stress on the analytical disciplinary approach come at the price of feeling attached to the collective and its history? The protocol shows that the Jewish discussant, who attempts an implicit distancing from Jewish identity ("Israeli is enough for me"), also expresses a disinterest in Jewish history ("it doesn't arouse interest in me…I did it for the exam…I don't care what I study"). By contrast, his peer declares herself a Palestinian Arab, and stresses her glorifying view of her people ("The Palestinians especially are very very very smart"). She also endorses emphatically learning the history of "My Arab country", by which she learns "very very wise things", and which she would "love others to study" it too. The contrast between the two learners suggests that some degree of identification and perhaps even glorification seems to motivate learning one's own national history. Furthermore, it seems that the Arab student who is more enthusiastic to learn about her own groups history also views learning the others' history more positively ("even when I study Jewish history…It's good, nice that I learn more"). Could the positive effect that feelings of pride and identification have on motivation to learn in-group history, be generalized to the out-group? Is there an essential relation between disidentification and emphasis on disciplinary practice? These questions are complex and do not seem to have general answers.

A: We in school study history, Jewish history, the Jewish

undergrounds and…but you don't study Arab history…why?

J: because we live in one state…state defined with one nation,

and which has one curriculum…

A: I live in this country and define myself as Palestinian Arab,

OK? You define yourself as Jewish, OK?

J: Israeli

A: Jewish Israeli

J: Whatever….Israeli is good enough for me

A: for you it is enough to study Jewish history, I define myself

as Arab I will learn only the Arab…

J: Call me narrow… but the fact I study something connected to

me, supposedly connected to me, the truth is it doesn't, it

doesn't arouse interest in me. I don't care which history. I did

it for the exam.

A: Not me. I, even when I study Jewish history…It's good, nice

that I learn more and more. But I study Jewish history and I

would love the others to study mine…

J: I agree with you

A: you know the Arabs, the Palestinians especially … are very

very very smart…So, I learn about my Arab country, I very very

very study very wise things.

J: first, l agree with you…I wouldn't mind studying another

history…but personally, if you ask me, I don't care what history

I would have studied.

Figure 1. An excerpt of a discussion in a

critical-inquiry condition that suggests that national

identification boosts the motivation to study own and others’

national history.

Figure 2 shows an excerpt of a discussion between two discussants

in the Narrative empathetic condition. They took the perspective

of the other, and frequently expressed feelings.

A: I have a question; if you were one of the great men in the

country or in Israel, would do you think you would have done?

J: Got it. I'd try to compromise on one decision

A: Which is? Come on…

J: Seems to me like the UN said- to split the land into two

parts so there would be peace and they wouldn't fight…that's

it…what do you think- what would you have done?

A: Me too, I think may be we could have reached a peace

agreement… …

J: Just a question right out of my head- how do you think the

Palestinians felt after they were deported?

A: Fear. No mother, no land, no one to turn to, that's how I

imagine myself if I was in their place at the time…nothing to

do, no power, no army, no leaders to supervise them or lead

them, nothing but themselves going where the Arab states or UN

tells them to go.

J: No one to lead them.

A: And that's scary, right.

Figure 2. Two discussants in the Narrative empathetic

condition exemplify they took the perspective of the other, and

frequently expressed feelings.

It is noteworthy that both attune themselves to the suffering of

the Palestinians, an orientation that apparently also facilitated

a more collaborative atmosphere. Perspective taking is used for

laying foundations for mutual trust, for discussing the possible

(although to some degree counterfactual) decisions of leaders and

for agreeing they would not fight as their predecessors had. The

second part of Figure 2 shows another phase in which the Jewish

discussant invites his Palestinian peer to relate to her and her

peoples' feelings, with which he appears to empathize. Both cases

of perspective taking show awareness of the difference and

distance between the historical agents and the learners (as

evinced by the use of the third person "them”), and of the action

of perspective taking ("that's how I imagine myself if I was in

their place at the time"). Emotion here is used as a venue into

the disciplinary practice of perspective taking. It is a cognitive

tool, directed at reconstructing the historical agents'

consciousness. This approach also aligns to some degree with the

movement between unicity and genericity, which drives forward the

process of "secondarisation" in dealing with tense social

phenomena (Muller Mirza et al., 2014).

It is worth comparing this discussion to a conversation in the conventional-authoritative condition. Figure 3 shows an Arab discussant responding in highly contentious and emotional manner to his Jewish peer's reconciliatory counterfactual speculation. Both discussants do not demarcate themselves from historical figures, but identify and "merge" with them through using first and second person plural, in what seems like a clear expression of collective memory. Discussants do not refer to the text they studied, nor do they analyse critically the evidence it contained. They rely on religious or mythical backings rather than on historical ones, impeding further deliberation of the question. Thus, it is in the context of teaching aimed at conveying a clear undisputed narrative that learning is emotionally disrupted and the past is disputed with no reliance on the discipline of history. The Jewish discussant, who initially adopted a more rational and more collaborative perspective, feels forced to gradually adopt a confrontational model.

J: That's what I think should have happened; we could get along,

you know what, even two separate states, one state for two

people and joint leadership and everything. No need to deport,

you know…at most we could have asked for some more territory so

it would be enough for two states.

A: But you didn't! you deported and murdered

J: And I'm saying, in my view there shouldn't have been

deportation

A: And you killed us and murdered us and stole and all this

J: I didn't do it and I think

A: You didn't do it but they did

J: I think it was a mistake and it shouldn't have been done in

no way…There were mistakes on both sides in the same way we

fought over our state earlier, and you fought for your state. We

both wanted something, basically the same. Each in his

direction.

A: OK. But you said you needed a state for the Jews, but why in

Palestine?

J: Because I said it, this place is sacred for me too, it is,

like my granddad’s granddad’s granddad he had here, they found

graves here, it's a place my ancestors lived in same as your

ancestors…this place is important to us, also sacred for us

too…I'm not a religious person and wouldn't go by the edicts of

Judaism in most cases but in the same way a Palestinian thinks

this place is sacred for the Palestinian people, it's a sacred

place for the Jewish people.

Figure 3. Two discussants in the

conventional-authoritative condition entertain a contentious

interaction.

Let us exemplify now another discussion in the

critical-disciplinary condition. Figure 4 shows an Arab discussant

who demonstrates his feeling of loyalty to his community as

mediated through the family. In spite of his declared impartiality

("you know, I don't distinguish between the texts") he points

quite clearly to his being an Arab as the reason for his

preference for Arab historian's excerpt. This preference is

accompanied by what seems like a confirmation bias – the tendency

to view evidence consistent with prior opinions as more reliable.

The Jewish participant on the other hand shows far lower

preference for in-group member's sources and founds his criticism

of sources on the practices he studied in the preparatory session

– sourcing and contextualization. We can see here how national

identity can bias historical practices such as evidence

evaluation. However, the critical inquiry approach encourages

participants to reflect on their evaluation of evidence and expose

their bias. It also seems that, at least for a member of the

dominant ethnic group, the critical inquiry approach promotes a

more balanced and impartial disciplinary practice.

A: Our opinion, I, because I'm an Arab, you know, I don't

distinguish between the texts, that of the Jew or the Arab, but

because my parents lived through it, they were in the time of

1948, I give more credibility to the text of written by the

Arab. I read there many things I already knew.

J: Your parents told you similar things?

A: Yeah…but what I read in the Jewish author's text was new, so

that's why…

J: OK. Personally, I too really believe the Arab author more.

A: What?

J: I too really believe the Arab author more because the Israeli

author writes… from a role of propaganda kind of, and from

within the ministry of foreign affairs and attempts to explain

Israel to the world, so it's in his interest to be in favor of

the Israeli side.

Figure 4. Two discussants in the critical-inquiry condition demonstrating identity motivated and disciplinary practice.

This paper initiates a reflection on the effects of emotions on oral argumentation for highly charged historical topics. The three pedagogical approaches exemplified in the protocols modelled different ways students handled emotions. The conventional authoritative single-narrative approach instils pride in one's nation and appears to delegitimize doubt and perspective taking. The empathetic dual-narrative approach facilitates mutual affirmation and increases the use of historical perspective taking, though not the use of critical thinking. The critical inquiry approach draws learners to reflect and expose the relation of their identity and emotions to disciplinary practices, and to some degree helps overcome it. Our claims cannot count as conclusions but as working hypotheses for further research. Moreover, this paper outlined the implications of various theoretical and empirical perspectives on the role of emotions in historical reasoning, fleshing them with actual discussion excerpts. We set forth the working hypotheses that these implications suggest. Firstly, history teaching that legitimizes the complex emotions arising from encounter with out-group perspectives by promoting strategic empathy and reflection on emotion (McCully, 2006; Zembylas, 2013), appears to promote productive deliberative discussions. This is perhaps because it affords more chances for mutual gestures helping maintain dialogue or because discomforting emotions help participants take the perspective of historical agents in troubled times (Zembylas & McGlynn, 2012). Engagement with emotion according to this approach seems to foster a nuanced and conscious use of perspective taking, though not necessarily better handling of evidence. Secondly, a direct attempt to expose the relation of identity-related emotions to historical practices, helps develop learners' internally persuasive dialogue and reflection about evidence (Barton & Mccully, 2010). This may promote critical thinking practices such as evidence evaluation. However, it does not insure curbing emotionally driven biases since evidence is used (perhaps with more restraint and awareness) in relation to identity needs and emotions (Goldberg, 2013; Gottlieb et al., 2005). Both these approaches promote a productive merging of emotion and cognition or reasoning (Mingers, 1991; Radford, 2015). By contrast, the conventional teaching approach, neither challenges nor acknowledges the role of collective emotion in learning (Barton, 2009). However, it appears to enhance or unleash its (negative) effect, both on learning and on deliberative discussion (Bless & Fiedler, 2006; Hilton & Liu, 2008). This may hint that relating to emotions holds a promise for better processing of information or deliberation of a historical question.

In summary, the examples presented suggest that emotion and identity do not necessarily constitute obstacles to deliberative discussions or disciplinary practice by themselves, in line with Baker et al.'s (2013) ideas. However, students in each approach engaged their emotions and learning differently. It appears that instructional practices moderate and influence the relations of emotion and reasoning. Facilitating empathetic listening, nurturing national glorification, or attempting to hold emotion at bay, may each lead to a different way of arguing about the past. We currently undertake an experimental study that involves the systematic comparison of discussions as well as of learning outcomes in the three approaches. The analyses we undertake will hopefully confirm and sharpen our working hypotheses.

Meanwhile, we believe that it is possible to rely on the above examples to draw some tentative conclusions on the teaching of History. History was introduced as a core discipline in schools in the 19th century in order to bring students to believe that they belong to a nation and to foster national pride (Ferro, 2004). We alluded to the experts' emotions-free list of core teaching practices and skills that reflect a substantial shift to the adoption of the norms of History as a critical rational discipline (Fogo, 2014). This shift does not pay attention, though, to the emotions history nurtures, arouses and is motivated by. The cognitive practices of history are nested within, colored by and interact with emotion (Maturana & Varela, 1987) As collaborative learning and disciplinary oriented practices take the lead in history teaching, the role of emotions becomes ever more important.

The protocols we presented suggest that while simply fostering the glorification of the nation impedes historical deliberation, concurring teaching approaches that bring to the fore alternative narratives and engage with strong emotions may actually help handle such influences. Therefore, educators should not dodge emotions in their teaching but, on the contrary, should capitalize on them to boost historical reasoning. The first place for bringing forward these strong emotions is of course the discussion. This setting risks bringing to the surface strong emotions (like anger), leading to breakdowns. However, the preparatory practices of engagement with both in-group and out-group perspectives, acknowledging and evaluating emotional overtones, seem to tone down contentious reactions when engaging in argumentation across groups.

With appropriate framing and instruction, students develop their capacity to handle emotions in discussions (Muller Mirza et al., 2014). They speak with each other, and deliberating together the historical roots of their conflict, even if their discourse was sometimes biased. We suggest, then, that the core practices of history teaching should also include addressing common opinions held by the different stakeholders on the issue, relating to the emotional states of the different historical actors and to the emotional reactions, of the learners (Bar-On & Adwan, 2006) and facilitating small group discussions across groups by helping the handling of emotions. These additional practices may promote the role of history in helping learners become citizens engaged in productive deliberation of their contentious past and their shared present.

Furthermore, we believe that research on historical understanding and reasoning should change both its prescriptive and its analytic stance to the role of emotions. First, if we wish to address the complexity of goals and needs history education addresses in reality (and not in an idealized rational expert model), it would serve researchers well to give emotion a more central role and treat it without disdain (Barton, 2009). Second, instead of relating to emotions and loyalties anecdotally, as indications of diverse identities, biased cognition or novice practice, there should be much to gain in exploring it proactively. Methodologically this means tracking and documenting emotion, whether through self-report or other implicit and observational methods now accessible through emotions research (see Baker et al., 2013). Analytically, we should start looking at emotions as promoters, factors and even as desirable outcomes of learning in history (Goldberg, 2013). This does not mean, of course, that we should ignore the inhibiting role of emotions in some cases, and that we should eliminate from class activity a detached critical-disciplinary approach. Our message is that emotions are precious resources for history education, but that teachers should learn when and how to capitalize on them.

Adwan, S., & Bar-On, D. (2004). Shared history project: A

PRIME example of peace building under fire. International

Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 17(3), 513-521.

Baker, M. J., Andriessen, J. E., & Järvelä, S. (Eds.). (2013).

Affective learning together. London: Routledge.

Bar-On, D., & Adwan, S. (2006). The psychology of better

dialogue between two separate but interdependent narratives.

Israeli and Palestinian Narratives of Conflict: History’s Double

Helix, 205-224.

Bar-Tal, D. (2007). Socio-psychological foundations of intractable

conflicts. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(11),

1430-1453.

Barton, K. C., & McCully, A. W. (2010). "You can form your own

point of view": Internally persuasive discourse in Northern

Ireland students' encounters with history. Teachers College

Record, 112(1), 142-181.

Barton, K. C. (2009). The denial of desire: How to make history

education meaningless. In L. Symcox, & A. Wilshcut (Eds.), National

history standards: The problem of the canon and the future of

teaching history (pp. 265-282). Charlotte, NC: Information

Age.

Bless, H., & Fiedler, K. (2006). Mood and the regulation of

information processing and behavior. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Affect

in social thinking and behavior (pp. 65-84). New York:

Psychology press.

Britzman, D. P. (2000). If the story cannot end: Deferred action,

ambivalence, and difficult knowledge. In R. Simon, S. Rosenberg

& C. Eppert (Eds) Between hope and despair: Pedagogy and

the Remembrance of Historical Trauma, (pp. 27-55). Lanham,

MD: Rowan and Littlefield.

Davis, O. L., Yeager, E. A., & Foster, S. J. (2001). Historical

empathy and perspective taking in the social studies.

Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Domke, E., Urbach, C., & Goldberg, T. (2009). Building a

state in the Middle East [Bonim medina baMizrach HaTichon].

Jerusalem, Israel: Zalman Shazar Center.

Eid, N. (2010). The inner conflict: How Palestinian students in

Israel react to the dual narrative approach concerning the events

of 1948. Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, 2(1),

55-77.

Evans, R. W., Avery, P. G., & Pederson, P. V. (1999). Taboo

topics: Cultural restraint on teaching social issues. The

Social Studies, 90(5), 218-224.

Ferro, M. (2004). The use and abuse of history: Or how the

past is taught to children. London: Routledge.

Fogo, B. (2014). Core practices for teaching history: The results

of a Delphi panel survey. Theory & Research in Social

Education, 42(2), 151-196.

Fox, E. (2008). Emotion science: Cognitive and

neuroscientific approaches to understanding human emotions.

Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goldberg, T., & Gerwin, D. (2013). Israeli history

curriculum and the conservative - liberal pendulum.

International Journal of Historical Teaching, Learning and

Research, 11(2), 111-124.

Goldberg, T. (2013). “It's in my veins”: Identity and disciplinary

practice in students' discussions of a historical issue.

Theory & Research in Social Education, 41(1), 33-64.

Goldberg, T., & Ron, Y. (2014). ‘Look, each side says

something different’: The impact of competing history teaching

approaches on Jewish and Arab adolescents’ discussions of the

Jewish–Arab conflict. Journal of Peace Education, 11(1),

1-29.

Goldberg, T., Porat, D., & Schwarz, B. B. (2006). “Here

started the rift we see today”: Student and textbook narratives

between official and counter memory. Narrative Inquiry 16(2),

319–347.

Goldberg, T., Schwarz, B. B., & Porat, D. (2008). Living and

dormant collective memories as contexts of history learning.

Learning and Instruction, 18(3), 223-237. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.04.005

Gottlieb, E., Wineburg, S., & Zakai, S. (2005). When history

matters: Epistemic switching in the interpretation of culturally

charged texts. Eleventh Biennial Meeting of the European

Association of Learning and Instruction,

Haskell, T. L. (1990). Objectivity is not neutrality: Rhetoric vs.

practice in Peter Novick's that noble dream. History and

Theory, 29(2), 129-157.

Helmsing, M. (2014). Virtuous subjects: A critical analysis of the

affective substance of social studies education. Theory and

Research in Social Education, 42(1), 127-140.

Hilton, D. J., & Liu, J. H. (2008). Culture and intergroup

relations: The role of social representations of history. In R. M.

Sorrentino, & Y. Susumu (Eds.), Handbook of motivation

and cognition across cultures (pp. 343-368). London, UK:

Academic Press.

Israeli Ministry of Education (2015). History curriculum for the

Jewish secular public schools. Retrieved March 2016 from

http://cms.education.gov.il/EducationCMS/Units/Mazkirut_Pedagogit/History/TochnitLimudimvt/TalTashah.htm

Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2000). Progression in historical

understanding among students ages 7-14. In P. N. Stearns, P.

Seixas & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching, and

learning history: National and international perspectives

(pp. 199-222). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Levstik, L. S. (2000). Articulating the silences: Teachers' and

adolescents' conceptions of historical significance. In P. N.

Stearns, P. Seixas & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing,

teaching, and learning history: National and international

perspectives (pp. 284-305). New York, NY: New

York University Press.

Maier, R. (2011). How we lived together in Georgia in the 20th

century- external evaluation EUROCLIO/MATRA project (2008—2011).

Retrieved from http://www.euroclio.eu/new/index.php/component/docman/doc_download/1080-how-we-lived-together-in-georgia-in-the-20th-century-external-review

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of

knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding.

Boston: New Science Library/Shambhala Publications.

McCully, A. (2006). Practitioner perceptions of their role in

facilitating the handling of controversial issues in contested

societies: A Northern Irish experience. Educational Review, 58(1),

51-65.

Mingers, J. (1991). The cognitive theories of Maturana and Varela.

Systems Practice, 4(4), 319-338.

Miron, A. M., Branscombe, N. R., & Biernat, M. (2010).

Motivated shifting of justice standards. Personality &

Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(6), 768-779.

doi:10.1177/0146167210370031

Muller Mirza, N., Grossen, M., de Diesbach-Dolder, S., &

Nicollin, L. (2014). Transforming personal experience and emotions

through secondarisation in education for cultural diversity: An

interplay between unicity and genericity. Learning, Culture

and Social Interaction, 3(4), 263-273.

National Center for History in the Schools. (2010). Historical

issues. Retrieved from http://www.nchs.ucla.edu/history-standards/historical-thinking-standards/5.-historical-issues

Radford, L. (2015). Of love, frustration, and mathematics: A

cultural-historical approach to emotions in mathematics teaching

and learning. In B. Pepin, & B. Roesken-Winter (Eds.), From

beliefs to dynamic affect systems in mathematics education

(pp. 25-49). New York: Springer.

Reisman, A. (2012). Reading like a historian: A document-based

history curriculum intervention in urban high schools.

Cognition and Instruction, 30(1), 86-112.

Saye, J., & Social Studies Inquiry Research Collaborative

(SSIRC). (2013). Authentic pedagogy: Its presence in social

studies classrooms and relationship to student performance on

state-mandated tests. Theory & Research in Social

Education, 41(1), 89-132.

Schwarz, B. B., & Asterhan, C. S. (2010). Argumentation and

reasoning. In K. Littleton, C. Wood & J. Kleine Staarman

(Eds.), International handbook of psychology in education

(pp. 137-176). London: Emerald Group Publishing.

Schwarz, B. B., & Goldberg, T. (2013). “Look who’s talking”:

Identity and emotions as resources to historical peer reasoning.

In M. J. Baker, J. E. Andriessen & S. Järvelä (Eds.), Affective

learning together (pp. 272-292). London: Routledge.

Sorek, T. (2011). The quest for victory: Collective memory and

national identification among the Arab-Palestinian citizens of

Israel. Sociology, 45(3), 464-479.

Thompson, J. (2014). Engaging girls’ sociohistorical identities in

science. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(3),

392-446.

Varelas, M. (2012). Identity construction and science

education research: Learning, teaching, and being in multiple

contexts. Springer Science & Business Media.

Wineburg, S. S. (2001). Historical thinking and other

unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past

Temple University Press.

Wineburg, S. S., Mosborg, S., & Porat, D. (2001). What can

Forrest Gump tell us about students' historical understanding?

Social Education, 65(1), 55-58.

Wohl, M. J., Branscombe, N. R., & Klar, Y. (2006). Collective

guilt: Emotional reactions when one's group has done wrong or been

wronged. European Review of Social Psychology, 17(1),

1-37. doi:10.1080/10463280600574815

Yaron, M. (2009). History superintendent's Requested

corrections to the textbook: Building a state in the Middle

East.[personal correspondence to author]

Zembylas, M. (2004). Emotion metaphors and emotional labor in

science teaching. Science Education, 88(3), 301-324.

Zembylas, M. (2013). Critical pedagogy and emotion: Working

through ‘troubled knowledge’ in posttraumatic contexts.

Critical Kambani Studies in Education, 54(2),

176-189.

Zembylas, M., &, F. (2012). The teaching of controversial

issues during elementary-level history instruction: Greek-Cypriot

teachers' perceptions and emotions. Theory & Research in

Social Education, 40(2), 107-133.

Zembylas, M., & McGlynn, C. (2012). Discomforting pedagogies:

Emotional tensions, ethical dilemmas and transformative

possibilities. British Educational Research Journal, 38(1),

41-59.