Frontline Learning Research Vol.11 No. 1 (2023) 1 - 39

ISSN 2295-3159

aThe University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Article received 14 June 2022/ Article revised 25 January 2023/ Accepted 25 January/ Available online 14 February 2023

Research shows that culturally diverse students are often disengaged in multicultural classrooms. To address this challenge, literatures on self-regulated learning and culturally responsive teaching both document practices that foster engagement, although from different perspectives. This study examined how classroom teachers at schools that enrol students from diverse cultural communities on the West Coast of Canada built on a Culturally Responsive Self-Regulated Learning (CR-SRL) Framework to design complex tasks that integrated SRL pedagogical practices (SLPPs) and culturally-responsive pedagogical practices (CRPPs) to support student engagement. Two elementary school teachers and their 43 students (i.e., grades 4 and 5) participated in this study. We used a multiple, parallel case study design that embedded mixed methods approaches to examine how the teachers integrated SRLPPs and CRPPs into complex tasks; how culturally diverse students engaged in each teacher’s task; and how students’ experiences of engagement were related to their teachers' practices. We generated evidence through video-taped classroom observations, records of classroom practices, students’ work samples, a student self-report, and teacher interviews. Overall findings showed: (1) that teachers were able to build on the CR-SRL framework to guide their design of a CR-SRL complex task; (2) benefits to students’ engagement when those practices were present; and (3) dynamic learner-context interactions in that students’ engagement were situated in features of the complex task that were present on a given day. We close by highlighting implications of these findings, limitations, and future directions.

Keywords: culturally diverse learners; engagement; self-regulated learning; culturally responsive teaching; complex task

This article reports findings from Aloysius C. Anyichie’s dissertation study at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. This novel study received the best 2019 dissertation award in Educational Psychology from the Canadian Ass ociation for Educational Psychology (CAEP).

Across North America, classrooms are increasingly including students from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds with diverse learning experiences and needs. Currently, there are too many experiences of systemic racism and inequality between mainstream and racialized minority students. Thus, this research is centrally concerned with how educators can create inclusive and equitable classrooms wherein every student is respected, experiences a sense of belonging, feels safe and is empowered to learn. For the research reported here, we considered that all students bring into the classroom their socio-cultural histories (e.g., ways of being and knowing) and practices including their previous experiences (e.g., of processes of learning in their previous schools and cultural environments), unique individual differences (e.g., interest), and expectations (e.g., about goals of learning, aspirations) that interact with classroom contextual features to shape their learning experiences including engagement (Anyichie, 2018; Bang, 2015; Butler & Cartier, 2018, Cartier & Butler, 2016; Gray et al., 2020; Gay, 2010; Graham, 2018; Okoye & Anyichie, 2008). In culturally diverse classroom contexts, students from non-dominant cultures are at greatest risk for a lack of engagement because classroom activities are often disconnected from their backgrounds, interests and lived experiences. Also, educators often struggle to create supportive learning environments for underrepresented and racialized learners (Gay, 2010; 2018). Given these challenges, research is needed to better understand how educators can design classroom environments to support culturally diverse learners’ engagement. Research on culturally inspired pedagogies and self-regulated learning are very helpful in this inquiry.

The diverse literature on asset-based culturally informed pedagogies (e.g., culturally responsive teaching, culturally relevant pedagogy) is helpful in how it foregrounds the influence of cultural background, heritage, and practices on individual learning processes (e.g., Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995, 2001; Villegas & Lucas, 2002). For example, research in culturally responsive teaching (CRT) reveals how classroom activities that are personally meaningful such as teaching skills or academic knowledge in ways that connect to students’ cultural knowledge, frames of reference and lived experiences increase their interest and offer support to culturally diverse learners (e.g., Gay, 2018). That said, most attention in this literature has focused on teacher practice in terms of the design and implementation of pedagogical practices rather than on how learners within those classrooms experience or engage with them. In addition, culturally sustaining pedagogy (Paris, 2012) emphasizes the need to sustain students’ languages, literacies, and the cultural ways of being in communities of colour in order to foster cultural pluralism and bring about positive social transformation (Paris, 2021; Paris & Alim, 2017). Scholars working from these different perspectives offer suggestions on how to address issues of educational inequality, power, systemic racism, social injustice, achievement gaps; and enrich learning experiences especially among racialized students and communities of colour (Andrews, 2021, McCarty & Brayboy, 2021, Howard, 2021, Paris, 2021; Young, 2010).

Another promising line of research, in terms of fostering culturally diverse learners’ engagement, focuses on self-regulated learning (SRL). SRL refers to individual and social forms of learning that empower learners to take control of their thoughts and actions in order to navigate environmental challenges and achieve valued goals (Zimmerman, 2008). SRL research has investigated how to empower learners’ participation by embedding SRL-promoting practices into learning activities (Butler et al., 2017; Dignath & Veenman, 2020). For example, SRL research shows that when students are provided with choice and opportunities to control the amount of challenge they are experiencing in an activity, gains ensue in engagement, agency, and achievement (e.g., Perry, 2013). SRL researchers are increasingly paying attention to how social and cultural contexts might be shaping the nature and quality of students’ learning experiences (Anyichie, 2018, Anyichie & Butler, in press; Anyichie et al., 2016; Hadwin & Oshige, 2011; Järvenoja et al., 2015; McInerney & King, 2018; Perry et al., 2017). But more research is needed into how educators can use SRL-promoting practices to create culturally responsive, relevant, sustaining, and inclusive environments and foster culturally diverse learners’ engagement and achievement.

Given their complementary foci, it might be generative to combine culturally responsive teaching (CRT) and self-regulated learning (SRL) practices to foster engagement for culturally diverse learners (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2017). Combining these practices has the potential to support engagement, motivation and active, intentional learning by informing the design of activities that are meaningfully relevant to learners’ socio-cultural histories, foster agency and empower learning (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2018; Gray et al., 2020; Gay 2013; Kumar et al., 2018). Activities that combine SRL and CRT practices could also be constructed in ways that sustain underrepresented students’ values, language and cultural practices while providing access to the dominant culture (Paris, 2021). Thus, the research conducted here investigated how the engagement of learners from culturally diverse backgrounds might be fostered in a classroom context that integrates self-regulated learning and culturally responsive pedagogical practices. The next section discusses how CRT and SRL pedagogical practices could be integrated into a classroom context to support culturally diverse students’ engagement.

Research from both the CRT and SRL fields identifies pedagogical practices that are associated with students’ engagement. First, although they emerge from different perspectives, frameworks such as culturally relevant pedagogy (e.g., Ladson-Billing 1995), culturally sustaining pedagogy (e.g., Paris, 2012), and culturally responsive teaching (e.g., Gay, 2010; Villegas & Lucas, 2002) all foreground the impact of sociocultural contexts on individuals’ learning process. Building on the understanding that learners tend to actively engage in classroom learning activities they perceive to be relevant to their cultural backgrounds and values, these frameworks suggest supportive practices. In particular, this study was inspired by CRT because of its emphasis on how to design classroom instructional practices to support learning for racialized and underrepresented students of colour (Gay, 2018). Some examples of culturally responsive pedagogical practices (CRPPs) include designing cultural diversity into curriculum content (e.g., by adjusting and situating curricula to connect with students’ prior knowledge and lived experiences by using multicultural textbooks), establishing cross-cultural communications (e.g., by creating opportunities for social interactions about personal or cultural issues), developing cultural competence (e.g., by fostering teachers’ and students’ understanding and knowledge of their cultures and that of other students), and creating cultural congruity (e.g., by using students’ cultural background and knowledge, histories, identities, frames of reference, interests, aspirations, and lived experiences as resources for teaching and learning) (Gay, 2013, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2021). These practices have been found to relate to student engagement, achievement and learning (Aceves & Orosco, 2014; Gay, 2018; Howard & Rodriguez-Minkoff, 2017; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Villegas & Lucas, 2002; Ginsberg & Wlodkowski, 2015). For example, Gray et al., (2020) found out that Black and Latinx students were more engaged in classroom activities that were relevant to their cultural values of communal benefits for learning.

As a complement to research on culturally responsive pedagogies, SRL research identifies practices that also support learning in context and foster engagement. Self-regulating learners are proactively engaged in their own learning process (Zimmerman, 2002). For example, they generate and implement relevant cognitive strategies for successful learning (Wolters & Taylor, 2012). SRL-promoting practices (SRLPPs) include giving students opportunities of making decisions about their learning; making choices and controlling the amount of challenge they are experiencing; engaging in formative assessments (e.g., self- and peer- assessment) and cycles of strategic action (e.g., task interpretation, goal setting, planning, enacting strategies, self-monitoring, strategy adjustment); and self-evaluating their work in relation to criteria. These practices are consistently associated with the quality of student engagement and success (Anyichie & Butler, 2015, in press; Anyichie & Onyedike, 2012; McCann & Turner, 2004; Perry, 2013; Schmidt et al., 2018). For example, Perry et al., (2020) reported that students with high levels of support for SRL (e.g., supports for self-assessment) in a writing task experienced higher levels of engagement in SRL resulting in a higher quality of writing product.

Historically, SRL models (e.g., Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Cartier & Butler, 2016; Efklides, 2011; Pintrich, 2000; Winne & Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2000) have foregrounded individual and social processes in learning. As one example, Butler and Cartier’s (2018) situated model of SRL emphasizes the role of dynamic interactions between what individuals bring to contexts (e.g., prior culturally-rooted experiences, histories, identities) and features of contexts (e.g., activity design) in shaping learning engagement. We drew on their situated model to offer a practical framework for developing an integrated pedagogy. Explicitly integrating a culturally-relevant, sustaining and responsive focus into research on SRL has the potential to further contribute by investigating how culturally diverse learners’ engagement can be supported when instructional practices are deliberately designed to facilitate both individual and sociocultural processes associated with learning (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, in press; Anyichie, et al., 2016).

To build on the practices identified in these two areas of research, “A Culturally Responsive Self-Regulated Learning (CR-SRL) Framework” (see Figure 1) was developed. This framework emerged from a theoretical and empirical analysis of the divergences and synergies between CRT and SRL principles and practices (see Anyichie, 2018, Anyichie & Butler, 2017 for the details of its development). This framework was designed to integrate these two areas of research as a support for educators who want to create supportive environments where new learning is built on learners’ prior knowledge, histories and lived experiences in ways that will motivate students to engage in co-construction of new knowledge. Research-based pedagogical practices that are integrated in this framework have been associated with gains in student engagement, motivation, SRL and achievement (Aceves & Orosco, 2014; Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2018, in press; Brayboy & Castagno, 2009; Elaine & Randall, 2010; Onyedike & Anyichie, 2012; Perry et al., 2020; Revathy et al., 2018; Wolters & Taylor, 2012).

Figure 1. A Culturally Responsive Self-Regulated Learning Framework

Source: Adapted from Anyichie (2018).

This framework includes three broad classes of practices that are mutually interdependent. First, classroom foundational practices refer to all those proactive activities educators put in place in setting up a classroom context to set the stage for a culturally relevant, responsive, sustaining, inclusive, and empowering classroom community. Foundational practices described in both CRT and SRL literatures include (1) fostering knowledge of learners; and (2) creating caring, safe, and supportive environments (Banks et al., 2005; Butler et al., 2017; Rahman et al., 2010). For example, “knowledge of learners,” as a strategy, refers to practices teachers employ to gain a better understanding of their students’ background histories and heritage (e.g., cultural identity, experiences, learning interests and needs, ways of knowing and being) that they can build on when designing instructional practices. Educators can start with activities like ice breakers, a know yourself game, or background surveys to gather some basic information about the students and their experiences (Anyichie, 2018). To better support culturally diverse students, educators need to develop their own cultural competence, and improve their awareness of students’ experiences of cultural diversity, issues of power, educational systemic racism, historical legacies of colonialism, and inequity. Educators can gain this knowledge by questioning their own individual assumptions, critically examining these socio-political issues and sharing ideas with others (Andrews, 2021; Ginsberg & Wlodkowski, 2015; Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Paris, 2012; Paris & Alim, 2017). These practices can generate a knowledge base that are more likely to help educators in creating a caring, safe and supportive environment that is responsive and relevant to the students’ cultural histories (Gay, 2018, Ladson-Billings, 2021). For example, knowledge of learners offers educators opportunities of connecting present learning to learners’ backgrounds and culturally situated lived experiences (CRPP), empowering students’ active engagement in co-construction of new ideas (SRLPP) and sustaining their ways of being (CRPP) (Paris & Alim, 2017).

Second, designed instructional practices are at the heart of this framework. These practices represent strategic combinations of SRLPPs and CRPPs within classroom environments or activities. SRLPPs (e.g., opportunities for making choices and exercising control over learning challenge) could be woven into learning activity to foster the meaningfulness and relevance of the task to students’ cultural background (CRPP). For example, an animal research project (e.g., on animal adaptation or habitation) with opportunities for students to choose an animal to research and decide how to demonstrate their learning can offer multiple prospects for diverse students’ engagement. Such animal project creates opportunities for diverse students to bring in their prior knowledge, lived experiences (e.g., about their chosen animal) and express their knowledge in ways that are relevant to their cultural practices. A “complex” task creates a rich context for integrating these practices.

Perry (2013) defines “complex” tasks as those learning activities that address multiple instructional goals (e.g., mastering learning content, writing and reading strategies); integrate across subject areas (e.g., science, social studies); focus on large chunks of meaning about the learning content (e.g., having an animal project that invites students to describe the animal habitat and generate relevant facts about their animal); engage students in making meaningful choices (e.g., topic to write about, who to work with in a group activity); involve students in cognitive (e.g., attention, thinking) and metacognitive processes (e.g., engagement in cycle of strategic actions); include individual and social forms of learning (e.g., working alone or in groups); and allow multiple ways of demonstrating knowledge and learning (e.g., drawing, writing, oral presentation) (Butler et al., 2017). Complex tasks can support students’ SRL. For example, an animal project could be deliberately designed as a complex task that connects with students’ cultural background and lived experiences (CRPPs); and empower their agency towards sustaining their cultural values and practices (SRLPP, CRPP), by providing opportunities for making choices and exerting control over learning challenges (SRLPPs).

Combining SRLPPs and CRPPs allow educators to establish cultural congruity and design culturally diverse curriculum context in their teaching (Gay, 2018). For instance, providing culturally responsive, relevant and sustaining choices within a complex task (SRLPP & CRPP simultaneously, such as asking students to choose an animal with cultural or religious relevance), and/or a sequence of CRPPs and SRLPPs woven into the same classroom learning activity has promise in fostering engagement in culturally diverse classrooms (Anyichie, 2018).

Finally, dynamic supportive practices describe the supports provided to students as their learning engagement unfolds in context. Dynamic practices can also weave together SRLPPs and CRPPs. For instance, students could be offered multidimensional feedback from teachers, peers and parents (e.g., identifying specific things that could be done to improve an on-going learning task) or using formative assessments (e.g., completing criterion-based self- and/or peer assessment forms) (Butler & Cartier, 2018; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) that are culturally relevant and sustaining (Egbo, 2019; Montenegro & Jankowski, 2017; Ladson-Billings, 2021).

Research has been identifying different ways that educators can design classroom contexts that build on this integrated pedagogy to support all learners’ engagement in multicultural classrooms (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2018; 2019; in press; Anyichie et al., 2019). For example, Anyichie (2018) conducted a pilot study to examine the potential of a CR-SRL framework in supporting culturally diverse learners’ engagement. In that study, he collaborated with a classroom teacher (i.e., Venus ) in a multicultural classroom in designing practices based on the CR-SRL framework. Analysis of classroom observations and documents showed that Venus was able to build from the framework to enact CRPPs and SRLPPs in her class that reflected each of the three dimensions, although how she did that differed across subject areas. Triangulation of multiple sources of data (e.g., classroom observations, teacher and student interviews, student surveys, experience sampling forms, student work samples) showed how culturally diverse learners’ engagement could be linked to the ways in which Venus enacted CR-SRL practices. Nevertheless, this first study was limited by a small sample size (e.g., one classroom; just one teacher and 6 of her students) and precluded the ability to conduct cross-contextual analysis. We designed the current study to involve parallel cases of two classrooms, teachers, and students to better examine how classroom contexts designed by educators who build from the CR-SRL framework might be instrumental in supporting culturally diverse learners’ engagement.

Engagement is a critical piece in understanding students’ learning experiences; and it is associated with many positive outcomes including students’ achievement (Appleton et al., 2008; Christernson et al., 2012; Fredricks et al., 2004; Fredricks et al., 2019; Kahu, 2013; Reeve & Tseng, 2011; Turner et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2019). There are variations in ways engagement has been conceptualized, defined, and studied (Appleton et al., 2008; Sinatra et al., 2015). Many researchers have come to define engagement as a multidimensional construct with three distinct but interrelated dimensions including affective/emotional, behavioural, and cognitive engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004, 2016; Wang et al, 2011). Behavioural engagement describes students’ overt behaviour and involvement in academic tasks and learning activities including attention, time on task, participation, concentration, and asking and answering questions (Fredricks et. al., 2004; Sinatra et al., 2015). Emotional engagement refers to students’ feelings, attitudes and reactions about classroom tasks including boredom, anxiety, frustration, sadness, interest, happiness, enjoyment and belonging (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012; Schunk et al., 2013). Cognitive engagement defines students’ deliberate investment of needed effort in their learning activities, metacognition, self-regulation of learning such as assessment, use of cognitive strategies, reflection, engagement in cycles of strategic action, active use of prior knowledge, and persistence in challenging tasks (Cleary & Zimmerman, 2012; Fredricks & McColskey, 2012). Recently, researchers have added attention to a fourth dimension, agentic engagement (e.g., Reeve & Tseng, 2011). Reeve (2013) defines agentic engagement as a “student-initiated pathway to a more motivationally supportive learning environment” such as active contribution to the flow of a learning activity including making suggestions and offering input (p. 581).

While these conceptual distinctions are common in self-reported literature (e.g., Jang et al., 2016), it can be difficult to observe and tease them apart in practice due to their overlap. For example, student emotional engagement (e.g., enjoyment) has been shown to be related to behavioural engagement (Pietarinen et al., 2014). There is also a correlation between cognitive and behavioural engagement (Martin, 2007; Wang et al., 2011); and they tend to overlap by involving effort. However, they can be distinguished by the nature of the effort expended. For instance, effort that involves doing the task (e.g., spending extra time) reflects behavioural engagement more than effort that is triggered by interest and motivation (e.g., deploying different strategies to master a challenging task or class material) which relates cognitive engagement (Fredricks et al., 2004).

Engagement has been studied separately in the fields of SRL and CRT. SRL research documents evidence that SRLPPs (e.g., choice provision, self and peer assessments) foster student engagement because they typically position students as owners of their learning while increasing their perceived autonomy (Montenegro, 2017; Patall et al., 2016; Perry et al., 2020). Research among culturally diverse students shows that students’ engagement is fostered through CRPPs (e.g., designing learning activities that are relevant to diverse learners’ prior knowledge and lived experiences) (Kumar, et al, 2018; Gray, et al., 2020). However, less research has been conducted about the integration of SRLPPs and CRPPs in supporting culturally diverse students’ engagement.

In addition, attention is drawn to using multiple approaches to measuring student engagement instead of depending only on self-report instruments due to the discrepancy between students’ report and their actual actions (Fredricks et al., 2019; Greene, 2015). Thus, this study adds to current literature on engagement by gathering multiple sources of data (i.e., quantitative and qualitative) to capture student engagement in classroom context that integrated SRLPPs and CRPPs.

Overall, student engagement involves a range of thoughts and actions that advance learning and lead to academic progress (Reeve, 2013). Due to the overlap among the different dimensions of engagement, limitations of self-report instrument, challenges of observing and making fine distinctions between forms of engagement in practice, for this study we operationalize engagement as an integrated construct that defines the process and the quality of a student’s active participation in a learning activity in relation to achieving task expectations.

Further, student engagement is malleable and situated in context (Fredricks et al., 2004; Salmela-Aro et al., 2016). For example, research has identified how a dynamic interaction between individuals and classroom contexts shapes learning experiences, including engagement and motivational processes such as interest, enjoyment and importance (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, in press; Butler & Cartier, 2018; Järvenoja et al., 2015; Nolen et al., 2015; Shernoff et al., 2016). Based on expectancy-value-theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000; 2020), utility-value intervention research (e.g., Harackiewicz & Priniski, 2018; Hecht, et al., 2021; Hulleman et al., 2010; Yeager et al., 2013) highlights the impact of students’ perceived usefulness or value of academic tasks on their engagement, interest, persistence, self-regulation, effort, and performance. Thus, in this study, we focused attention on how culturally diverse students’ overall engagement could be associated with their perceived contextual features including values of activities that educators built into their practice in terms of being interesting, enjoyable and important.

The purpose of this study was to examine how two teachers were able to integrate SRLPPs and CRPPs into complex tasks so as to support their culturally diverse students’ engagement. Our research questions were: (1) How did the teachers integrate CRPPs and SRLPPs in complex tasks? (2) How were culturally diverse students engaging in those complex tasks? and (3) How was culturally diverse students’ engagement related to the CR-SRL practices enacted?

This study involved two parallel case studies situated in elementary classrooms (i.e., one grade 4; one grade 5) within which teachers designed complex tasks to support culturally diverse learners’ engagement. A case study design was chosen because of its effectiveness in examining a complex, dynamic and multidimensional phenomenon as it manifests in situ (Merriam, 2009; Yin, 2014). For instance, case study designs provide a framework for understanding students’ learning processes and the connections between pedagogical practices and associated outcomes (e.g., engagement and motivation) (Butler, 2011; Butler & Cartier, 2018). A case study design also allowed us to collect and coordinate multiple forms of evidence to examine individual and social processes as they unfolded in the context of tasks.

To recruit teachers as participants from multicultural classrooms, the lead author of this article reached out to an Independent School Board located in an urban community in a western province in Canada. He already had an existing professional relationship with the School Board. He discussed his plans to volunteer as a resource person for supporting teaching and learning in upper elementary multicultural classrooms, and future intention of conducting research with interested teachers. The choice of upper elementary classrooms was to include students with the maturity to articulate their cultural backgrounds and learning experiences. The School Board provided him with a total list of four schools they identified as multicultural within the district. With School Board permission, the lead author e-mailed principals of six schools, including the four suggested by the school Board as well as two other schools where he already had professional connections. Three principals accepted his offer for help and extended his invitation to their teachers. He visited the schools of these principals out of which two teachers indicated interest to participate in this study.

Ultimately the lead author visited the classes of upper elementary teachers, who volunteered to participate in this study, at two of those schools (Joseph and Matthias, respectively) . Joseph taught in a grade 4 classroom at St Mary’s elementary; Matthias taught in a grade 5 classroom at St. Victor’s elementary school. Table 1 shows demographic information for each teacher as well as teaching experiences.

Table 1

At the time of this study, the province in which these teachers’ schools were located was transitioning to a new curriculum that focused on personalized learning, project-based learning, and accommodating student diversity including cultural backgrounds. In this context, the teachers shared the goal of empowering culturally diverse learners to engage actively in more personally relevant, open forms of learning. Still, in relation to this study, both teachers did not have any formal knowledge or experience about designing CRPPs and SRLPPs. In addition, although Joseph was experienced with designing complex tasks, Matthias had never designed a complex task for his class.

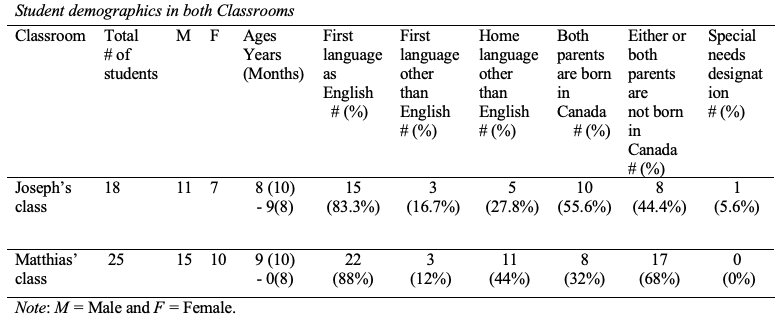

3.2.1. Students in Joseph’s classroom

All students in Joseph’s Grade 4 classroom (n = 31) were invited to participate in this study. Eighteen students volunteered to participate by submitting back their signed assent and parent/guardians’ consent forms. Table 2 shows that these eighteen participants were between the ages of 8 and 9. Tables 2 and 3 combine to show how Joseph’s students came from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds.

Table 2

Table 3

3.2.2. Students in Matthias’ classroom

All 31 students in Matthias’ Grade 5 classroom were also invited to participate. Of them, twenty-five provided parental consent and assent to participate in the study. Table 2 shows that these participants were between 9 and 10 years of ages. Tables 2 and 3 combine to show the diversity in students’ identified first and home languages, countries and ethnicities.

The lead author of this article worked with the two volunteer teachers across the Fall 2017 to design complex tasks that enacted CR-SRL promoting practices. He met with each of the two teachers separately (Joseph and Matthias) and discussed their research interests and goals for students. Next, the lead author served as a collaborator in facilitating individual meetings with each teacher separately. To advance teachers’ professional learning and practice development, he drew on a collaborative inquiry framework to involve them in the cyclical processes of goal identification, planning and enacting practices, reflecting on progress, and refining approaches accordingly (Butler & Schnellert, 2012; Timperley et al., 2014).

More specifically, during early meetings, the lead author introduced the CR-SRL framework (Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2017) and discussed with each teacher how it could be implemented to support culturally diverse students’ engagement. Through those discussions, he collaborated with each teacher in sharing ideas about designing and enacting relevant practices (i.e., CRPPs and SRLPPs), both for their classrooms as a whole and for a particular task. In each case, he focused on building from each teacher’s prior learning and experience. For example, based on the curriculum, what the teachers were already doing and experimenting with in relation to designing an integrated pedagogy, he worked with each teacher to design a learning task of their choice.

He also worked together with the teachers throughout the term in refining the tasks in ways that best accommodated the provisions of the CR-SRL framework. As students’ learning unfolded, he supported participating teachers to refine their practices as it fitted the dynamism of their respective classes. Overall, each teacher had control over how to integrate the CRPPs and SRLPPs within their chosen learning activity as they considered appropriate for their students.

3.3.1. Co-designed complex tasks

The co-designed complex task in Joseph’s class was titled Understanding Animal and Human Adaptations to the Land. This learning task had three sections: animal adaptations, First Nations’ adaptations to the land, and students’ adaptations to school. The first section asked students to research adaptations of any animal of their choice. The second required them to research human adaptations with the First Nations in Canada as a case example. Finally, building on what the students were learning about animal and human adaptations, the third section asked them to research their personal adaptation to school.

The co-designed complex task for Matthias’ students was titled Understanding your Personal and Cultural Identity. This learning task also had three sections: relationships and cultural contexts, personal values and choices, and personal strengths and abilities. Each of these sections comprised three to five open-ended questions that students were expected to answer. Part of the first section also asked the students to create a collage that described them culturally (see Appendix A for details on each of these tasks).

As part of his early conversations with teachers, the lead author identified all proposed research procedures, but then made modifications based on their negotiation of goals and processes. Following the completion of all ethical procedures, he worked with each teacher separately to implement the study design. Further, prior to data collection, he explained all the data collection measures and processes to the students in Joseph’s and Matthias’ classes and invited them to participate. He provided the teachers with consent/assent forms for themselves, their students’ parents/guardians, and their students. He explained to the students that the purpose of the study was to investigate with their teachers how best to support their learning. Finally, he observed and collected data about the participating teachers’ implementation, and students’ experiences, of the CRPPs and SRLPPs.

For each case study, we collected and coordinated multiple sources of data including: (1) classroom observations and associated field notes; (2) teacher documents (e.g., task instructions); (3) student work samples; (4) students’ self-reports about their engagement using an Experience Sampling and Reflection Form (ESRF); and (5) teacher interviews.

3.5.1. Observations

The lead author conducted 12 observations of instructional episodes of complex task across 9 days in Joseph’s classroom (515 minutes), and 6 observations across 5 days in Matthias classroom (255 minutes). Observations focused on the practices Joseph and Matthias enacted to support culturally diverse students in the context of their tasks; and how the students were participating in those practices. Each observation lasted between 30 and 80 minutes. The total number of observations in each class was dependent on the number of days teachers invited the lead author to observe their students. Observing the same students over time offered an opportunity to understand their engagement as related to the specific features of their complex tasks.

During each classroom observation, the lead author created a running record of what he observed (see Perry,1998; Anyichie, 2018). In those records, he tried to capture all teacher and student talk “verbatim” as much as he could during individual and small group activities. He video-taped observations when it was possible to capture only students who had consented to participate. Those video-taped observations provided rich contextual information and helped to better understand and interpret students’ engagement. While circulating during an observation, the lead author occasionally debriefed with the students about their participation. He also debriefed with teachers after each observation to gain more understanding about their practices in relation to students’ participation in them.

3.5.2. Teacher documents

The lead author reviewed the complex task instructions to consider practices each teacher designed to support his students. The review of this documentation assisted him during observations to focus attention on students’ participation in relation to teachers' enactment of CRPPs and SRLPPs.

3.5.3. Student work samples

During the observations, as students were working on their tasks, the lead author photographed samples of their work. Sometimes, he took pictures of drafts in their work folders. These pictures helped to see how students were participating in the tasks in relation to features of each specific section.

3.5.4. Experience sampling and reflection form (ESRF)

We used an ESRF adapted from (Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014) to gather students’ self-reports of their experiences while participating in the complex task. This form asked questions about students’: (1) feelings (i.e., how did you feel about working on this activity today?); (2) concentration (i.e., how well did you concentrate while working on this activity/task today?); (3) perceptions of challenge (i.e., was this activity challenging for you? If so, what made it challenging? What did you do about the challenge?); (4) perceptions of importance (i.e., how important is this activity?); (5) perceptions of enjoyment (i.e., did you enjoy what you worked on today?); and (6) interest (i.e., was this activity interesting?). Students rated their subjective experiences on 5-point Likert scales from 0 (not at all) – 4 (very much). They also provided explanations for their ratings by responding to a follow-up “why”? Students filled out this form each time they worked on their tasks to help them reflect on their experiences while sharing that with their teachers. Asking them to immediately report their experiences reduced retrospective bias. These repeated reports also helped us and the teachers to understand students’ real-time experiences over time. Overall, the students submitted ESRF (n = 77) in Joseph’s class; and (n = 94) in Matthias’ class.

3.5.5. Interviews

The lead author, at the end of the study, conducted individual in-depth semi-structured interviews with each teacher. The teachers were asked to share their perceptions about the practices they designed. Example questions included: What CR-SRL classroom practices did you design and implement to support your students, especially culturally diverse learners in your multicultural classroom? What did you try that seemed successful and beneficial? Why do you think it was effective? What challenges did you experience? Their interviews took place at the teachers’ schools and lasted between 45 - 60 minutes.

We conducted a combination of qualitative (e.g., of classroom observations, teachers’ debriefing and interviews, document, and student work samples) and quantitative (e.g., of student self-reports/ratings on the ESRF) analyses.

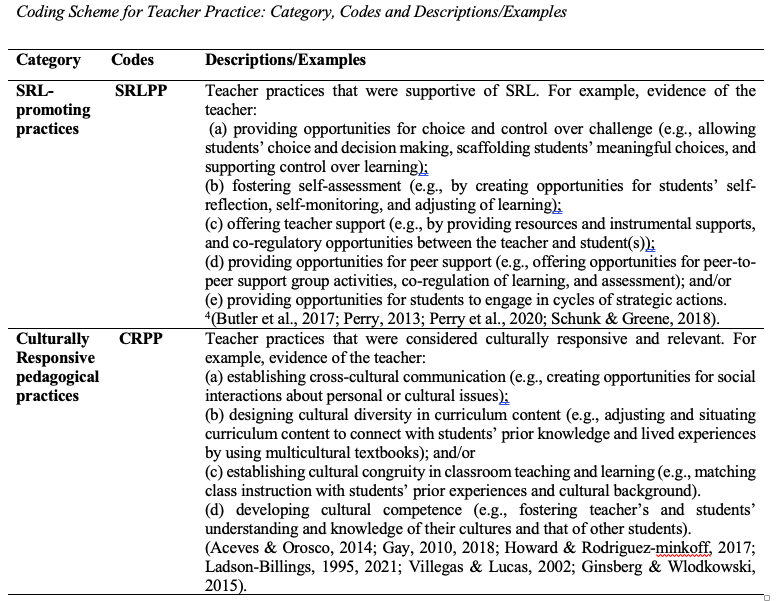

3.6.1. Coding of teacher practices

We transcribed video-taped classroom observations, debriefings, and semi-structured teacher interviews. The transcribed information was shared with the teachers who confirmed the content before the coding. We reviewed documents (e.g., complex task instructions) and student work samples. We worked together to develop a priori categories derived from the CR-SRL framework (see Anyichie, 2018, Anyichie & Butler, 2017 for detailed review) to inform coding but were also open to unexpected findings. To support this analysis, we engaged in two levels of coding.

First, we developed a chronological list of all practices enacted in each instructional episode with references to the lesson, activities, and section of the complex task. Then we looked at each practice from an SRL point of view, flagging any practice consistent with SRL-promoting practices (see Table 4). Subsequently, we again reviewed the full list of practices with a CRT lens, flagging any practice clearly linked with CRT principles. The result was a chronological list of practices flagged as SRLPPs, CRPPs, both, or neither. This approach to coding enabled us to interpret whether and how SRLPPs and CRPPs were intertwined within each lesson and section of the task (see Table 5).

Second, once all lessons, sections and activities were coded, we categorized the practices in relation to the three main categories of practices identified in the CR-SRL framework (i.e., foundational, designed instructional and dynamic supportive practices). This lens enabled us to interpret how the practices teachers enacted did (or did not) reflect the main kinds of practices most frequently identified across the SRL and CRT literatures. Finally, documents and fieldnotes were mined for confirming or disconfirming evidence.

3.6.2. Coding of students’ engagement

We coded, analyzed and interpreted students’ engagement in the context of the complex tasks based on three sources of data: (1) observations of students’ engagement, (2) students’ work samples, and (3) students’ reflections (using the ESRF).

To code observational data, we reviewed field notes and transcripts of debriefs to describe student activities and identify instances of their participation in specific contexts. We looked for engagement that reflected any of the four dimensions of engagement, as identified earlier, but did not try to disentangle them. For example, we coded as engagement evidence of students’ participation and direct involvement in learning activities including effort and persistence (e.g., reading, note taking and re-writing); concentration and focusing attention (e.g., eyes fixed on worksheets with evidence of thinking and writing); reflection and assessment (e.g., completing self/peer assessment forms); help-seeking (e.g., asking questions), listening and answering questions, making suggestions and offering input in class, and thinking aloud. Finally, we examined student work samples for traces of engagement (e.g., integrating teacher feedback). Whenever we flagged a link between teachers’ practices and engagement in our displays, we then accessed other forms of data in search of patterns to understand how particular practices (e.g., CRPPs, SRLPPs) may have enabled different students’ engagement in specific contexts. Although we did not calculate inter-rater agreement, the first and second author discussed and reached agreement on the coding processes.

We also measured student engagement by analysing their self-reported responses to the ESRF. We started by constructing a display of each student’s ratings on concentration (as another indicator of engagement). To consider how their concentration ratings were linked to their perceptions of the complex task (and the section they were working on), we also looked at their perceptions of challenge, enjoyment, importance, and interest. Then, we calculated descriptive statistics. We also created displays that allowed us to see how students’ perceptions about their tasks shifted across days and were associated with their self-reported concentration. To examine if variations in students’ self-reported perceptions and engagement were similar within and across days, we conducted repeated measures within subject analyses of variance.

Furthermore, to advance our understanding of the possible associations between students’ perceptions of, and engagement in their tasks, we conducted correlational analyses. Finally, to support identifying patterns, quantitative data from the ESRF were roughly interpreted to be low if below midpoint (< 2.5) and high if above midpoint (>2.5).

Table 4

Table 5

3.6.3. Links between students’ engagement and the contextual features of the complex task

To trace the links between teacher practices and students’ engagement during their respective complex task, we created data displays highlighting the relationship between teachers’ practices on different days and students’ self-reported engagement using matrix coding queries in Nvivo 11 software. The displays represented observations of teacher practices alongside students’ narrative description of their perceptions of teacher practices and their participation on the ESRF.

4.1. How did teachers integrate CR-SRL practices into their complex tasks?

The review of teachers’ instructions for the complex tasks and classroom observations combined to reveal that both teachers integrated CRPPs and S0RLPPs into their classrooms to support their students’ engagement. However, they integrated these practices in different ways. This section starts by presenting the findings in Joseph’s class as a foundation for comparing the similarities and differences with Matthias’ class.

4.1.1. Joseph’s class

Joseph integrated both SRLPPs and CRPPs across sections of the complex task he designed. For example, part of the instructions for his task asked students to:

Research one of the Aboriginal People (e.g., Inuit, Metes and First Nations). Compare your findings about the First Nations and our daily living by responding to these questions: What is the biggest difference? What is most surprising when I think of my life? If I was a First Nation person my age, what would I enjoy the most? (CRPP)

The above instructions revealed that Joseph supported his students’ learning about Aboriginal people in relation to their own lived experience (CRPP). He offered them an opportunity to conduct independent research about Aboriginal peoples (SRLPP) and compare their research findings with their individual life experiences (CRPP and SRLPP).

Part of Joseph’s complex task also involved the students in a field trip to a local museum to see exhibitions of the Aboriginal peoples, especially the First Nations [task instructions]. After the trip, Joseph asked his students to reflect on their personal experiences and learning by completing a worksheet with some guiding questions (e.g., “Find 3 things that helped the First Nation peoples in their daily lives, provide a drawing, a brief description”; “How is this object/thing different from what you use in your life”; “How is my life changed after I have seen these exhibits”?) (CRPP). Further, the students were asked to share their individual learning in small groups and present their groups’ collective learning through a podcast to the entire class (SRLPPs) [task instructions; observation Day 9]. This example shows how Joseph created opportunities for his students to connect this task with their sociocultural context through the field trip (CRPP), and their personal lived experiences (CRPP and SRLPP) through self-reflection (SRLPP).

Overall, Joseph’s task provided varied opportunities for students’ learning and engagement. It contained almost all the features of a complex task as defined by Perry (2013) (SRLPPs). For example, it engaged students in independent and social forms of learning (e.g., individual and small group research), integrated two subject areas (e.g., Science and Social Studies), extended over time (i.e., over two months), allowed students multiple ways of demonstrating learning and knowledge (e.g., through a multimedia book, podcasts presentations and role play), focused on large chunks of meaning about the learning content (e.g., conducting research), and involved students in making meaningful choices (e.g., of the Aboriginal People to research, what and how to share about their lived experiences in relation to the First Nation Peoples’ lives) [task instructions; observations]. But Joseph also strategically wove CRPPs in these SRL-supportive features (e.g., by linking content to students’ cultural backgrounds and lived experiences). Joseph provided scaffolds for students’ engagement in completing the task such as generating ideas (SRPP), activated their prior knowledge in a way that facilitated students’ connection of class activities to their lived experiences (CRPP), and offered opportunities for students’ self-reflection, self- monitoring and peer support (SRPP).

4.1.2. Matthias’ class

Like Joseph, Matthias integrated both SRLPPs and CRPPs into the different sections of his learning task. For example, his instructions in the section on “Personal Values and Choices,” asked students to: (1) list 5 things that are important to you/that you value in life; (2) explain why each of them is important to you; (3) consider “What do you hope to be in the future, and why?”; and (4) reflect on “How is this hope affected/influenced by your values or your cultural background? If it isn’t, what affects/influences your hope and why?” Through these instructions, Matthias provided opportunities for students to deliberately connect this class activity to their cultural background and personal lives (CRPP), make personally meaningful choices and exercise control over the information they were sharing (SRLPP), and reflect on how their culture might be influencing their choices and values in life (SRLPP and CRPP).

Also, the section titled Culture Collage asked students to “make a collage of images and words that describe and represent you culturally (CRPP); …use the space below [worksheet] to brainstorm ideas that you can apply to your final collage” (SRLPP) [task instruction; observation Day 4]. This evidence suggests that Matthias offered opportunities for his students to engage in strategic action and self-monitoring (SRLPP) and bring their cultural and life experiences into classroom learning activities (CRPP).

That said, whereas Joseph’s learning task advanced his students’ understanding of classroom topics by situating them in their cultural backgrounds and lived experiences (CRPP), Matthias’ task, as a foundational practice, focused most on developing his students’ awareness and understanding of their identities and cultural backgrounds (e.g., by creating a collage) (CRPP). Matthias’ task did include some of the features of SRL-promoting “complex” tasks (Perry, 2013). For example, the task included multiple sections with specific products, involved students in both independent and small group learning processes, and extended over time (SRLPPs) [task instructions; observations]. However, whereas the activities in Joseph’s task were highly integrated and interdependent, Matthias’ task consisted of a series of short, similar tasks in a survey format. The activities involved mostly open-ended questions and built only from the Social Studies curriculum. Also, Matthias’ task had limited instructional goals, opportunities for group activities and demonstration of learning in multiple ways. Overall, Matthias’ task did not include a rich combination of SRLPPs and CRPPs compared to that of Joseph.

To understand students’ in-the-moment perceptions about their participation during the complex tasks, we examined their ESRF reports including both (1) students’ self-reported concentration (as one indicator of engagement); and (2) whether they perceived the task on each day as challenging, interesting, important, and/or enjoyable. In this analysis, we interpreted these latter ratings as indicators of how they were responding to the practices built into the task each day as personally relevant, valuable, and meaningful.

4.2.1. Joseph’s class

Table 6 shows that students who participated in the CR-SRL Complex Task in Joseph’s class reported high-levels of engagement across all five days when ESRF data were collected (concentration, M = 3.20, SD = 0.74). They also perceived the task to be highly important (M = 3.53, SD = 0.87), interesting (M = 3.36, SD = 1.18), and not very challenging (M = 0.74, SD = 0.90). Their perceptions of the task as highly important and interesting suggested that they may have found it personally meaningful, valuable, and relevant (M = 3.50, SD = 0.80).

To find out if the differences in student mean ratings were consistent across days, or instead varied in relation to specific sections of the task, we ran a repeated measures Analysis of Variance on each of concentration, importance and interest. The results of the repeated measures ANOVA with sphericity assumed showed that there were no statistically significant differences at the p < .05 level for student ratings across days on Concentration [F (4, 28) = 1.116, p = .369, η2 =.138]; Importance [F (4, 20) = 1.117, p = .376, η2 =.183], and Interest F (4,12) =1.131, p = .388, η2 = .274). These findings suggest that, overall, the students in Joseph’s class perceived the CR-SRL complex task to be highly important and interesting and were very engaged in it across days.

Table 6

4.2.2. Matthias’ class

Table 7 shows that students in Matthias’ class reported relatively high levels of engagement in their complex task on days when the ESRF was collected (Concentration, M = 2.97, SD = 0.17). A repeated measures ANOVA showed that there were no statistically reliable differences in self-reported concentration across days [F (3, 54) = 2.568, p = .064, η2 =.125]. That said, while students’ ratings were above the mid-point, suggesting relatively high levels of engagement, their self-reported concentration was significantly lower than that reported by students in Joseph’s classroom (M = 3.20, SD = 0.74).

Overall, Table 7 also indicates that Matthias’ students perceived the task to be very important (M = 3.04, SD = 0.07), enjoyable (M = 2.94, SD = 0.36), and interesting (M = 2.75, SD = 0.30). Students’ overall perceptions of the task suggest that they found it to be personally meaningful, valuable and relevant (M = 2.91, SD = 0.22). However, as in Joseph’s classroom, there were some variations in their perceptions of the task across days. For example, although repeated measures ANOVA showed that students reported similar levels of importance across days [F (3, 51) = .504, p = .681, η2 =.029], post hoc pairwise comparison analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment indicated that the students reported higher levels of interest and enjoyment on Day 4 as compared to Day 6 (interest, p = .041; enjoyment, p = .012). This finding again points to the way in which classroom conditions including teacher practices influenced students’ perceptions of a complex task over time.

Table 7

To answer our third research question about the links between students’ perceptions of the complex task (i.e., interest, enjoyment, importance, challenge) and engagement, this section presents for each class: the association between students’ perceived values of daily activities and their self-reported concentration (i.e., one indicator of engagement); and a case study analysis of engagement as linked to activities on days where the highest variation was observed.

4.3.1. Joseph’s class

4.3.1.1. Associations between students’ self-reported engagement and perceptions about the complex task.

To better understand how students’ perceptions of the complex task (i.e., interest and importance) could be associated with their self-reported concentration, we conducted a correlational analysis (see Table 8). Results indicated that all three variables were positively inter-correlated, suggesting a positive relationship between students’ perceptions of the task and engagement in Joseph’s classroom.

4.3.1.2. Associations between students’ engagement and teacher practices in the complex tasks.

To gain more insight into the links between Joseph’s practices and students’ engagement across days, we started by reviewing all evidence of students’ engagement in their tasks on each day, including students’ ratings and written reflections on the ESRF, classroom observations/ debriefs, and student work samples. We cross-referenced that data with evidence of Joseph’s practices derived from classroom observations/debriefs, task instructions, and his teacher interview. For the most part, students’ engagement in Joseph’s task was high. Although there were high-levels of student engagement across days, in this section, we chose Day 8 for more in-depth analysis, since it was the day we observed the greatest variation in students’ perceptions of the task (see Table 6).

Case study of Day 8. Prior to Day 8, Joseph had asked the students to conduct independent research on the First Nations’ ways of life and share their findings in small groups. On Day 8, they focused on comparing their research findings about the First Nations’ life and their individual lives [task instructions; observation]. Joseph had two connected activities in his lesson: brainstorming and completing a worksheet (See Table 9).

Joseph’s practices on Day 8. During the complex task on Day 8, Joseph enacted both SRLPPs and CRPPs (See Table 9). For example, he spent the first 10 minutes facilitating a brainstorming activity about how the First Nations lived and adapted to their land, and how that might be similar or different from today’s way of life [observation] (CRPP). He supported students’ thinking about the First Nations’ ways of life through metacognitive questions (SRLPP): and retention of generated ideas by writing all their responses on the white board [observation]. Observational data indicated that while scaffolding students’ reflective thinking (SRLPP) about how to compare First Nations’ way of life and how people live today including themselves (CRPP), the teacher instructed them to: “…think about the most dramatic differences you come up with, most important to the least important”.

The second activity asked the students to compare their own life experiences with that of the First Nations by generating at least 3 similarities and differences (CRPP) [task instruction; observation]. Joseph supported students’ completion of this activity through a structured worksheet. For this activity, he gave them choices about how and where to work saying: “It’s lot more of individual work, but you can work with your partner to get at least 3 similarities and differences,” and at any corner of the class or at the Resource room (a room adjacent to their class) (SRLPP) [observation]. As the students completed their worksheets, Joseph was observed circulating from group to group and answering questions. Occasionally, he scanned through their worksheets and offered encouragement by saying “good, good.” At one point, after visiting a group, he shared an idea from S5: “He says that the First Nations people hunted for food, but we hunt for sport. Yet, we get food from it [hunting], but have it for sport” (CRPP). In this way, he offered instructional support by sharing an idea from a student and by facilitating conversations around it (SRLPP).

Linking student engagement to teacher practices on Day 8. Overall, our analysis suggested that student engagement was related to the CRPPs and SRLPPs Joseph enacted on Day 8. We observed that most of the students were actively engaged during the lesson activities. For example, at the beginning of the lesson, the students asked and answered questions and updated their notes. This finding could be linked to the open-ended questions Joseph posed to them during the brainstorming exercise, as well as recording their responses on the board (SRLPPs). During the second group activity, students in one group were observed taking turns in comparing their lives with that of the First Nations, as well as negotiating ideas to be written in their main worksheet. We observed this kind of negotiation among other groups as well. This involvement in co-construction of ideas could be associated with the opportunity Joseph created for students to connect classroom activities to their lived experiences (CRPPs) and to collaborate in completing the structured worksheet (SRLPPs). Our interpretation was validated by Joseph who connected the level of his students’ engagement to the practices he enacted: “I found in this project that having students relate what they learned to their self … was very effective and had a high-level of engagement” [interview, 18/12/2017].

Although the students were engaged during this lesson, examination of their reflections on the ESRF showed mixed and contradictory perceptions about that part of the task (see Table 9). Their comments, which can be associated with the variations in their engagement on Day 8, could be attributed to individual differences and preferences in relation to the activities (e.g., whether or not they liked the content or lack of access to technology, and how they felt about it). For example, 4 out of 15 students that submitted their ESRF on this day reported feeling bored. These variations and individual differences may explain the overall lower self-reported concentration on this day compared to other days.

Table 9

4.3.2. Matthias’ class

4.3.2.1. Associations between students’ self-reported engagement and perceptions of the complex task.

To better understand how students’ perceptions of the complex task’s value could be associated with their self-reported concentration in Matthias’ class, we again conducted a correlational analysis. The results in Table 10 indicate that students’ perceptions of the task were positively and statistically significantly correlated with each other, but not with their reports of concentration. This finding suggests that the relationship among the students’ perceptions of the task on a given day notwithstanding, the complex task in Matthias’ classroom may not have consistently led to an increase in students’ concentration. This finding contrasts with that of Joseph’s class where engagement correlated positively with students’ perceptions of the learning task.

Table 10

Case study of Day 6. We chose Day 6 to better understand the interaction between Matthias’ practices, in which students’ self-reported perceptions and concentration varied greatly on that Day (see Table 7). On Day 6, the students came in from the lunch break, and submitted an assignment that asked them to write a paragraph on comics (Language Arts). Next, while seated at their lockers [arranged in a table format with four/five students facing each other], the students independently worked on the section of the task on “Personal Strengths and Abilities” [observation]. This section focused on students’ understanding of their strengths and abilities and how they use them in their community.

Teacher practices on Day 6. Classroom observational data showed that Matthias enacted CRPPs and SRLPPs on Day 6 (see Table 11). To begin, he spent the first few minutes introducing the section of the task the students were supposed to be working on and communicating that he expected them to finish that section that same day. As in previous sections of the task, on Day 6 students were charged with answering open-ended questions: (1) “What are some of your strengths and abilities?”; (2) “What would you say are some of your challenges and weaknesses?”; and (3) “How are you using your strengths in your: family, school, relationships?” (CRPP) [task instructions]. Next, he distributed a worksheet containing the above three questions as a learning resource to students (SRLPP) [observation].

Table 11

Our observational data showed that while the students were completing their worksheets, Matthias concurrently facilitated a brainstorming exercise, strategically guiding the students through each of the questions in the worksheet. Occasionally, Matthias allowed limited time in between the questions for students to write their responses on their worksheets. Within that short period, he circulated, asked questions, and attended to students’ specific needs. Similarly, he provided scaffolds by asking questions (e.g., What do you think are your strengths?) (CRPP/SRLPP) and facilitated students’ learning and retention by keeping track of generated ideas on the board. Matthias supported students’ attention and concentration by celebrating a student’s achievement: “You see she [S3] just focused and got finished. If you pay attention and reduce your discussions, you will be done soon”. Halfway through the lesson, Matthias facilitated students’ thinking about situating their responses in the context of their home and lived experiences: “How are you using your strengths at home? So, if you are creative, maybe during festive times you are helping out at decoration of things... think of things you do at home…” (CRPP). Although the questions in the worksheets were designed to orient students’ thinking in a culturally relevant manner, Matthias did not explicitly emphasize making that connection all the time. Finally, towards the end of the activity, before submitting their work, Matthias created an opportunity for students to reflect on their perceptions of the activity in terms of being personally meaningful, valuable, and relevant through the ESRF (CRPP/SRLPP).

Linking student engagement to teacher practices on day 6. Observational data showed that many of the students were somewhat passive during the lesson activity. For example, during the brainstorming exercise, most students sat quietly on rows, listened, looked at the board and wrote in their worksheets. Occasionally, some other students asked clarification questions to the teacher (e.g., “What if I want to write being empathetic”, “Can we write full sentences?”). Also, not many students responded to teacher directed questions. This observed low-level engagement could be associated with the fact that Matthias talked more often than students, including responding to some of his own questions, while supporting students’ task interpretation and completion. In addition to teacher practices, students’ experiences with previous sections of the task (i.e., which also involved many written responses) may have impacted their interest and added to their lower-level engagement (see Table 11).

Examination of student worksheets showed how they made personally relevant choices about the information they were sharing (see Figure 2). This finding could be linked to the metacognitive questions Matthias provided in the student worksheet (CRPP/SRLPP). Yet, students provided similar responses in some questions. For example, many of the students stated “athletic, curiosity, creativity, confidence, and empathetic” as their strengths [observation; student worksheets]. This resemblance in student responses could be associated with the teacher’s efforts to keep track of their brainstorming discussions by writing generated ideas on the board. Since Matthias always guided his students through each of the questions with little time for them to deeply reflect on the questions, the students may have depended on teacher support and relied on his recording of ideas on the board. Inadvertently, Matthias’ procedural support (Perry, 1998) may have caused dependency and constrained individual students’ thinking beyond their collective class discussion; thereby giving rise to passive participation and experiences of boredom. From an SRL perspective, the activity on Day 6 could be described as mostly teacher directed, with limited opportunities for bridging from guiding learning to fostering students’ independence. There was also no observed opportunity for social interaction or peer feedback. At the end, however, the ESRF (see Table 11) seemed to support their thinking, reflection on the activity (linked to SRLPPs), and awareness of their identities (linked to CRPPs).

Figure 2. Student work samples on strengths and abilities

These findings in Matthias’ classroom like those from Joseph’s class, again suggested that the dynamic interaction between the learner and context shaped their students’ engagement. In Matthias’ class, the low engagement level of students on Day 6 appeared to be related at least in part to the ways in which he enacted CRPPs and SRLPPs. Fewer of those practices were evident on Day 6, when compared with other days (e.g., Days 4 and 5). Interestingly, while in Joseph’s class most students reacted positively on most days to the learning task, Matthias’ task was not as consistently successful in engaging learners. In Matthias’ classroom, there was greater variability in students’ perceptions and responses to the same learning context.

In relation to our first research question, findings indicated that both Joseph and Matthias built on the CR-SRL framework and wove CRPPs and SRLPPs in their independent complex tasks. Although each teacher had a choice of how they integrated CRPPs and SRLPPs, we expected this finding since the teachers volunteered and collaborated with the lead author in building from a CR-SRL framework to co-design a complex task to support their students’ engagement. This finding suggests how participating teachers were learning to think about integrating CRPPs and SRLPPs simultaneously within a learning activity. Also, it is in line with other research that has shown that teachers who are mentored to implement SRL and/or culturally responsive frameworks, and are supported to work using a collaborative inquiry framework (Timperly et al., 2014), experience shifts in their instructional approaches (Butler et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2006; Teemant et al., 2011; Powell et al., 2016; Correll, 2016).

That said, we observed differences in how Joseph and Matthias designed and enacted their tasks that seemed consequential in terms of influencing students’ engagement. For example, evidence suggested that Joseph embedded a wider variety of CRPPs and SRLPPs with the potential to engage his students than did Matthias. The differences in observed practices could have been influenced by the differences in their teaching experience, comfort levels with experimenting with new instructional practices, and the needs of their students. For example, Joseph, who had been teaching for over 20 years, was already familiar with designing a complex task [debriefings], and with little support from the first author was able to successfully weave in CRPPs and SRLPPs. On the other hand, Matthias, who had been teaching for 8 years, described himself as a novice in designing complex tasks [debriefings]. As a result, his learning task eventually included fewer features of an SRL-promoting “complex task” than did Joseph’s (Perry, 2013). This finding is consistent with those of other studies that have linked teachers’ experimentation with new instructional strategies and shifts in instructional practices with teaching experience, participation in in-service professional development/workshops, collaborative inquiry and/or collaborations with researchers (Anyichie & Butler, 2017; 2018; Butler & Schnellert, 2012; Clark et al., 1996; Gray et al., 2020; Mor & Mogilevsky, 2013; Turner & Trucano, 2015). This study adds by showing how the CR-SRL framework helped teachers to build from their prior experience to start weaving CRPPs and SRLPPs together in generative ways into learning tasks and classrooms.

One of the major findings from this study was that student engagement in the CR-SRL Complex Tasks in each classroom was relatively high. Furthermore, findings showed a higher level of engagement in Joseph’s classroom, where the use of the two kinds of practices were more frequent and interconnected. Research on both CRPPs and SRLPPs has similarly suggested that these practices are associated with higher levels of engagement and motivation (Ginsberg & Wlodkowski, 2015; Kumar et al., 2018; Wolters & Taylor, 2012). Also, this research adds by showing how CRPPs and SRLPPs could be combined within learning tasks to support high levels of engagement. Overall, the findings of this study extend the literature by showing that an increase in student engagement can be associated with an integrated CRPPs and SRLPPs (e.g., Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2017, 2018, in press; Anyichie et al., 2016; 2019; Gay, 2018; Ginsberg & Wlodkowski, 2015; Perry, 2013; Revathy et al., 2018). In terms of the underlying goal of this research, which was to investigate strategies for more consistently supporting engagement of culturally diverse learners, this finding is very encouraging (see also Anyichie, 2018; Anyichie & Butler, 2018).

This research also adds by tracing with some specificity how students’ high level of engagement in their tasks could be associated with how teachers combined CRPPs and SRLPPs. For example, students in both Joseph’s and Matthias’ classrooms, while working on their tasks, were highly engaged in making culturally relevant choices. Students’ engagement in choice making could be associated with opportunities teachers provided. For example, students were asked to make choices of what to learn and how to demonstrate their learning (SRLPP, Joseph); they were given opportunities to choose how to respond to culturally relevant open-ended guided questions (CRPP, Matthias). By making these choices, students participated in exercising control over their learning tasks. They also bridged the gap between their home and classroom cultures by deliberately connecting classroom activities to their histories and backgrounds. For instance, Matthias’ culturally situated guiding questions (CRPP/SRLPP) activated his students’ prior knowledge, fostered their metacognitive thinking, and supported them in making personally relevant decisions about their values, strengths, and future life goals based on their interests, ability, family needs, and lived experiences. These kinds of questions might create opportunities for the sustainability of students’ cultural practices and ways of being in their communities (Paris, 2021).This finding adds to previous literature on the association between choice provision, motivation, and engagement (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2018; Evans & Boucher, 2015; Jiang, et al., 2021; Patall et al., 2016; Perry, 2013) by revealing the affordances of a CR-SRL Complex Task for student choice making and control over learning. Overall findings from this study suggest the power of culturally relevant, sustaining, and meaningful choices in enhancing learners’ engagement.

As culturally diverse students’ participation in the learning task unfolded in both classrooms, our findings showed that they were highly involved in self-reflection and self-assessment. For example, they situated their reflections on what they were learning in relation to their cultural backgrounds and lived experiences. In addition, they self-assessed their learning contexts (e.g., the task) and self-reported their perceptions and participation in them on the ESRF. Through these reflective processes, students engaged in cognitive and metacognitive processes by analyzing and monitoring their learning performances in ways that seemed to foster their active engagement in the task. This finding connects with previous research showing how self-evaluation and formative assessment improve students’ engagement, SRL, cognitive processes and achievement (Andrade & Valtcheva, 2009; Braud et al., 2021; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Perry et al., 2010, 2020; Sanchez et al., Cooper, 2017; Schunk & Zimmerman, 2008). This study adds by showing how CRPPs can foster students’ self-reflection. Further, consistent with previous research (e.g., Anyichie, 2018, Anyichie & Butler, 2018; 2019; in press), students’ engagement during self-reflection processes could be linked to the opportunities teachers created (e.g., by providing culturally relevant questions) for students to relate what they were learning to their cultural backgrounds and lives (CRPP/SRLPP). Similarly, Aceves and Orosco (2014) found that student engagement, understanding of text, and reading achievement increased when the teacher in their study created opportunities for students to relate the context of their reading activity to their individual background knowledge and lived experiences. This finding connects with the current study by suggesting how engagement can be enhanced in a personally relevant and valuable learning activity.

Furthermore, findings from observational data showed that Joseph engaged his students by providing opportunities for independent and group activities that allowed for social interaction and sharing, peer support and collaboration (SRLPP), as well as connecting classroom activities to their cultural backgrounds (CRPP). Both teachers, as well, offered instrumental support (SRLPP) by providing scaffolds for students’ metacognitive thinking about how the tasks could be connected to their cultural backgrounds (e.g., through provision of worksheets with open-ended questions, and brainstorming activities). These findings align with those of other studies that have documented how student engagement is fostered by activities that involve collaboration, teacher support and new learning (Cooper, 2014; Heemskerk & Malmberg, 2020; van Braak et al., 2021; Klem & Connell, 2004; Parsons et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2013). Our study adds by suggesting how culturally mixed small group activities, if implemented with responsivity and respect, could amplify students’ engagement.

Our findings also revealed a dynamic interaction between the learner and context that shaped students’ learning engagement. Specifically, findings showed that students’ perceptions of their classroom activities in terms of being personally relevant and important, most times, shaped their engagement in them. For example, the complex task in Joseph’s classroom more reliably fostered students’ positive perceptions and higher levels of self-reported concentration, which were associated with CRPPs and SRLPPs and how he wove those in a more complex way. However, student reflective explanations of their experiences revealed individual-context variations within class engagement levels. These variations were more pronounced in Matthias’ than in Joseph’s classrooms and could be attributed to individual differences (i.e., preferences) in relation to the quality of activities assigned on particular days (e.g., teachers’ use of CRPPs and SRLPPs), and the overall learning context (e.g., being distracted by peers) across days.