Introducing Real-Time Indeterminate Synthetic Music Feedback (RT-ISMF) as a Therapeutic Intervention Method

Keywords:

Psychotherapy, Real-time Indeterminate Synthetic Music Feedback, random event generator, quantum noise signals, PK feedbackAbstract

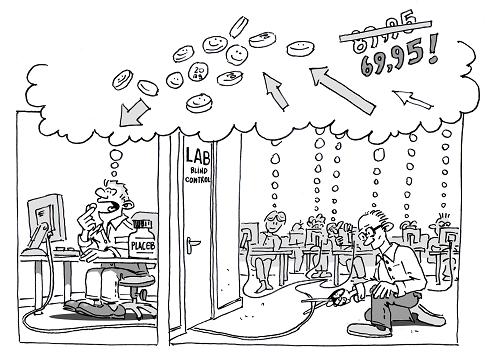

Started in 2007, partly unpublished artistic research has resulted in the development of a Psi-related collection of methods and instruments, which features possible applications in healing and therapeutic intervention2. This article will introduce this collection of methods and instruments, under the name Real-time Indeterminate Synthetic Music Feedback (RT-ISMF). The ISMF system generates indeterminate music by transforming quantum noise signals from a REG (random event generator) into uniformly distributed musical scales, note durations, and note values. The music produced in this way may serve as a continuous micro-PK feedback system, in which the music is the carrier of information produced by the REG (see illustration 1). Listeners to ISFM music have reported deep relaxation in short times. Dream-like images, visions, voices, and sudden insights are experienced, most of them connected in a remarkably meaningful way to important issues in the individual’s life. Since 2008, ISMF has been used during formal and informal therapeutic settings like psychological intervention, individual empowerment, relaxation and ‘healing.’ Evidence for possible applicability as a therapeutic intervention method has been collected from case studies and group events during which ISMF music was central. Case studies show that ISMF may be an effective intervention for a broad range of psychological, yet unclassified discomforts. Combinations of ‘exceptional experiences’ as well as spiritual and bodily healing are reported. ISMF and the supporting therapeutic interviewing technique have not been documented in publications so far. This article sketches the history, the design and theoretical background of ISMF. Case studies in which ISMF was central are summarized.References

William James (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Routledge, 2008, p. 240.

Iebele Abel (2010). Informationele Technologie in Therapeutische Context. Tijdschrift voor Parapsychology en

Bewustzijnsonderzoek, no. 1, 2010, pp. 21-24. (Informational Technology in Therapeutic Contexts, Dutch Journal for

Parapsychology and Consciousness Research).

Martin Wuttke (1992). Addiction, Awakening, and EEG Biofeedback, Biofeedback, Vol. 20, No. 2, June 1992.

The used REG is the Quantum Random Number Generator, developed by idQuantique, Switzerland. This REG is based on

counting reflection and transmittance of photons on a semitransparent mirror.

The artistic and philosophical aspects of this project are discussed in detail in Iebele Abel (2009, 2013), Manifestations of

Mind in Matter. Conversations about Art, Science, and Spirit. Princeton: ICRL Press.

W. Braud, & M. Schlitz (1983), Psychokinetic influence on electrodermal activity. Journal of Parapsychology, 47, 1983, pp.

-119.

The author has not checked reports of clairvoyance.

David M. Wulff (2001). Varieties of Anomalous Experiences: Examining the Scientific Evidence, ed. Etzel Cardeña, Steven

Jay Lynn, and Stanley Krippner. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Associationp, p. 413.

In "A world with retroactive causation" Dick Bierman (Systematica, 1988, Vol 7, 1-7,) argues that there is empirical

evidence that effects can precede causes.

See also: Dick Bierman& Dean Radin (2000), Anomalous unconscious emotional responses: Evidence for a reversal of the

arrow of time, Towards a science of consciousness III: The Third Tucson Discussions and Debates, (ed. S. Hameroff, A.

Kaszniak, & D. Chalmers). Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Garret Moddel, Zixu Zhu and Adam M. Curry, Laboratory Demonstration of Retroactive Influence in a Digital System, AIP

Conference Proceedings, 1408, pp. 218-231.

James Pritchett (1993). The Music of John Cage. Music in the 20th Century. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge

University Press. p. 108.

Daryl Bem (2010). Feeling the Future: Experimental Evidence for Anomalous Retroactive Influences on Cognition and

Affect, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 100(3), 2010, p. 407.

Annemiek Vink (2001), Music and Emotion, Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 10:2, 2001, p. 145.

There are however indications that music is an effective means for ‘mood induction’ and ‘mood manipulation.’ See for

references: Marcel Zentner et al. (2008), Emotions Evoked by the Sound of Music: Characterization, Classification, and

Measurement, Emotions, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2008, p. 494.

See chapter 3 of Kenneth E. Bruscia (1998), Defining Music Therapy. Second Edition. Barcelona Publishers (USA).

Annemiek Vink (2001), Music and Emotion, Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 10:2, 2001, p. 150.

There are, on the other hand, studies out of the scope of this article that point to the physical basis of intentional healing

systems targeted on the physiology of the body, which do relate to ISMF. In a general form Roger Nelson describes this

physical basis as: “When there is a disruption, and healing is required, the need is for additional order, the infusion of

information.” See: Roger Nelson (1999), The Physical Basis of Intentional Healing Systems, PEAR Techical Note 99001,

January 1999.

Leonard B. Meyer (1956). Emotion and Meaning in Music. The University of Chicago Press, pp. 6-7.

For therapeutic use, “associative texts” concerning ISMF should therefore be used with caution, because “associative

text” or any kind of interpretation related to the ISMF instrument and the music it produces, would infringe its ‘pure’

nature.

Stephen Davies (2006). Artistic Expression and the Hard Case of Pure Music, Contemporary Debates in Aesthetics and the

Philosophy of Art, ed. Matthew Kieran. Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp. 177-179.

Partik Juslin and John Sloboda (2013), Psychology of Music (ed. Diana Deutsch), Academic Press (Elsevier), 2013, pp. 583-

As an example of (partly) conveyed emotion (as opposite to elicited emotion) used in therapeutic settings I quote from an

article about Helen L. Bonny’s Guided Imagery and Music psychotherapy: “… the music therapist assesses the current

emotional state of the client, and then chooses a classical music program which will first match that state in sound.” See:

Lisa Summer (1992), Music: The Aesthetic Elixir, Journal of the Association for Music and Imagery, 1(1), 1992.

Marcel Zentner et al (2008), Emotions Evoked by the Sound of Music: Characterization, Classification, and Measurement,

Emotions, 2008, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2008, p. 514.

Marcel Zentner et al (2008), Emotions Evoked by the Sound of Music: Characterization, Classification, and Measurement,

Emotions, 2008, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2008, p. 515.

Thomas Hillecke; Anne Nickel; Bolay, Hans Volker Bolay (2005), Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, Vol.1060, 2005, p. 276.

Thomas Hillecke; Anne Nickel; Bolay, Hans Volker Bolay (2005), Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1060, 2005, p. 280.

Thomas Hillecke; Anne Nickel; Bolay, Hans Volker Bolay (2005), Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1060, 2005, p. 275.28 M.J. Lambert (1992), Psychotherapy outcome research: implications for integrative and eclectic therapists, Handbook of

Psychotherapy Integration. (ed. J.C. Norcross & M.R. Goldfried), pp. 94–129. Basic Books. New York. Reference taken from

Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2005, Vol. 1060.

Thomas Hillecke; Anne Nickel; Bolay, Hans Volker Bolay (2005), Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1060, 2005, pp. 277.

Thomas Hillecke; Anne Nickel; Bolay, Hans Volker Bolay (2005), Scientific perspectives on music therapy, Annals of the

New York Academy of Sciences, 2005, Vol.1060, 2005, pp. 278.

H. Walach et al. (2009), Spirituality: The Legacy of Parapsychology, Archive for the Psychology of Religion, vol. 31, p. 286.

H. Walach et al. (2009), Spirituality: The Legacy of Parapsychology, Archive for the Psychology of Religion, vol. 31, p. 285.

Friedman and Krippner notice that “regarding the issue of methodology, it is amazing in itself that advocates and

counteradvocates, both credible on their own terms, can look at the same data and draw vastly different conclusions. (…)

people with different worldviews could look at the same data and interpret them in widely divergent ways.” See Stanley

Krippner and Harris L. Friedman (2009), Debating Psychic Research, Praeger, p. 202.

Dean Radin and Roger Nelson (2000), Meta-analysis of mind-matter interaction experiments: 1959 to 2000, Boundary

Institute, Los Altos, California Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research, Princeton University, p. 9.

Stefan Schmidt et al. Distant intentionality and the feeling of being stared at: Two meta-analyses, British Journal of

Psychology (2004), 95, p. 245.

Larry Dossey (2007), PEAR Lab and Nonlocal Mind: Why They Matter, Explore, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 193-194.

Many studies found evidence for nonlocal healing. See for a list of studies notes 29-76 in Larry Dossey (2007), Explore, ,

Vol. 3, No. 3, pp.195-196.

Russel Targ & Jane Katra (1990,1998), Miracles of Mind, p. 231.

Braud, W. & Schlitz, M. (1983). Psychokinetic influence on electrodermal activity. Journal of Parapsychology, 47, pp. 95-

Concepts like consciousness or information ‘fields’ inspire many people, but I wonder if the metaphor ‘field’ is right to

describe the phenomena in which consciousness and reality impinge on each other. See also Iebele Abel (2009-2013),

Manifestations of Mind in Matter, ICRL Press, pp. 125-126.

Russel Targ & Jane Katra (1990,1998), Miracles of Mind, pp. 251-253.

Robert G. Jahn (1996), Information, Consciousness, and Health, Alternative Therapies, No. 3.

Luke Hendricks (2010), The Healing Connection: EEG Harmonics, Entrainment, and Schumann’s Resonances, Journal of

Scientific Exploration, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 420.

See also section ISMF music and Emotion.

A. Martin Wuttke (1992), Addiction, Awakening, and EEG Biofeedback, Biofeedback, Vol. 20, No. 2.

Russel Targ & Jane Katra (1990,1998), Miracles of Mind, p. 124.

Russel Targ & Jane Katra (1990,1998), Miracles of Mind, p. 124.

S. Gröblacher et al. (2007), Nature 446, p. 871. Refered to by Dean Radin (2012), Physics Essays 25, 2.

Dean Radin, Leena Michel, Karla Galdamez, Paul Wendland, Robert Rickenbach & Arnaud Delorme (2012), Consciousness

and the double-slit interference pattern: Six experiments, Physics Essays 25, 2.

H. Walach et al. (2009), Spirituality: The Legacy of Parapsychology,Archive for the Psychology of Religion, vol. 31, 2009, p.

See: C.J. Ehman, (2009), Spirituality & Health: Current Trends in the Literature and Research. University of Pennsylvania

Medical Center (Web), and Andrew J. Weaver et. Al (2006), Trends in the Scientific Study of Religion, Spirituality, and

Health: 1965-2000, Journal of Religion and Health, Volume 45, Issue 2, June 2006, pp. 208-214.

This definition was endorsed by the WHO in resolution EB 10 1.R2 (1998). See: M.H. Khayat (1999), Spirituality in the

Definition of Health: The World Health Organisation’s Point of View;J.L.F. Gerding (2013), Filosofische bespiegelingen rond

spiritualiteit, Universiteit Leiden, p. 8; James Larson (1996), The World Health Organization's definition of health: Social

versus spiritual health, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 38(2), 1996, pp.181-192.

Cicero, De Divinatione. Book II, 5.

Hélène L. Gauchou, Ronald A. Rensink , Sidney Fels (2012), Expression of nonconscious knowledge via ideomotor actions,

Consciousness and Cognition, vol. 21, 2012, p. 980.

Wouter J. Hanegraaff (ed. 2005). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Volume I. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005,

p. 225.

Wouter J. Hanegraaff (2003). How Magic Survived the Disenchantment of the World, Religion 33.4, p. 361.

Wouter J. Hanegraaff (2005). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Volume I. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005, p.

Wouter J.Hanegraaff (2005). Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Volume I. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005, p.

Francesca Rochberg (2010). In the Path of the Moon, Babylonian Celestial Divination and its legacy, Studies in Ancient

Magic and Divination, Vol. 6, Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2010, p. xxi.

Chance and determinability separates events that are of interest of divination and which are not. See Cicero, De

Divinatione, Book I, 5:14: “Divination is the foreseeing and foretelling of events considered as happening by chance.” Events

that are due to natural causation are excluded from divination; see Book II, 14:34 and 19:44.61 Textbooks containing lists of artifacts have been found near Fara, Iran/Afghanistan. Artifacts appear frequently as omen

protasis in Sumerian literature. See Samuel Noah Kramer, Cultural Anthropology and the Cuneiform Documents, Ethnology,

:3 (1962:July) p. 307.

The correspondence principle that theories must agree with experimental evidence in physics, and the theological idea of

correspondences, meaning that spiritual and physical realities are related, is but another example of historical continuity of

correspondence in scientific thought with ‘different aim and content.’

Ervin Schrodinger(1944). What is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell. Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 68, p.

-85.

I refer here to the ‘Yates paradigm’ according to which changing attitudes towards ancient knowledge - and the hermetic

tradition (including theory of correspondences) in particular - have significantly shaped the direction of scientific progress.

The ‘Yates paradigm’ has come in for legitimate criticism. See Antoine Favre and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (1998), Western

Esotericism and the Science of Religion. Leuven: Peeters, 1998, p. XIII-XIV.

For the Babylonian priests everything could be read as a sign. Theologians of Jewish, Muslim and Christian traditions gave

higher regard to prophecies, but still enjoin believers to reflect on the natural world and its movements in order to discover

signs from God’s omnipotence. See Amur Annus (2010), Divination and interpretation of signs in the ancient world, The

Oriental institute of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Seminars, Number 6, 2010, Chicago, Illinois, 2010, p. 12-13.

As an example Jaques Monod states that “Chance alone is at the source of every innovation, of all creation in the

biosphere” in Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology (1972), pp. 112-113.

Including control over their fellow men. See for the relation between governmental control and statistics: Barry Smart

(2004): Michel Foucault, Routledge, 2004, the chapter On Government, p. 129: “One of the forms of knowledge which

developed to provide a knowledge of the state, namely statistics, became a major component of the new technology of

government.” See also: Michel Foucault (1975): Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison, and, more specifically related to

healthcare practice: Hans Achterhuis (1988): De markt van welzijn en geluk.

Although the classification of diviners as ‘scientists’ would probably not make sense to, for example the ancient

Babylonian, from our current position the ancient intellectual tradition was ‘theory laden’ and featured with empiricism

and systematization of knowledge. See: Francesca Rochberg (1999). Empiricism in Babylonian Omen Texts and the

Classification of Mesopotamian Divinations as Science, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 119, No. 4, 1999, p.

and p. 565.

Wayne B. Jonas & Harald Walach (2007). From Parapsychology to Spirituality: The Legacy of the PEAR Database, Explore,

Vol. 3, No. 3, May/June 2007, p. 197: “Science marched its own way, trumpeting its favorite tune ‘Matter is All, and We Will

Show You Why.’ The scientific community stomped every evidence to the contrary in the ground – such as produced by the

Society for Psychic Research.”

Jaques Monod, note 66.

See Kuhn’s Structure for a definition of normal science p. 80 (normal science brings fact and theory to closer agreement).

The domain of normal science is limited to problems that only lack of ingenuity keeps them from being solved (p. 37.)

Thomas S. Kuhn (1922). The structure of scientific revolutions.University of Chicago Press, 1996.

KnutGraw (2006). Locating Nganyio Divination as Intentional Space, Journal of Religion in Africa, 36.1, 2006, p. 78, 113.

The term ‘own divination’ is taken from Rudolf Otto (1917), Das Heilige. Über Das Irrationale In Der Idee Des Göttlichen

Und Sein Verhältnis Zum Rationalen.Dutch translation, Het Heilige (2002), p. 240.

Roderick Main (1997), Encountering Jung. On Synchronicity and the paranormal. Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 101.

This term was introduced by C.G. Jung. Jung defined synchronicity in a variety of ways. To mention some: “Meaningful

coincidence”, “acausal parallelism”, or “acausal connecting principle.” See Roderick Main (2007), Revelations of Chance:

Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology, 2007, pp. 14-17.

Jung, Briefe III, 1973, p. 283 (my translation from C.G. Jung, Herinneringen, Dromen, Gedachten, Lemniscaat, 2010, p.

.

C.G. Jung (1967).Ges. Werke VIII, p. 105, 576. (Reference from C.G. Jung, Herinneringen, Dromen, Gedachten,

Lemniscaat, 2010, pp. 372-373).

Roderick Main (2007). Revelations of Chance: Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal and

Humanistic Psychology, 2007, pp. 39-62.

Roderick Main (2007). Revelations of Chance: Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal and

Humanistic Psychology, 2007, p. 62.

Roderick Main (2007). 2007, Revelations of Chance: Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal

and Humanistic Psychology, p. 60.

Roderick Main (2007). Revelations of Chance: Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal and

Humanistic Psychology, 2007, p. 58.

C.G. Jung (1921). Collected Works. Vol. 6, Psychological Types. Routledge, 1971, p. 474.

Avery Dulles (1983). Models of Revelation, Gill land Macmillan. Referred to by R. Main (2007), p. 59.

Roderick Main (2007). 2007, Revelations of Chance: Synchronicity As Spiritual Experience. Suny Series in Transpersonal

and Humanistic Psychology, p. 148; C.G. Jung (1950). The I Ching or Book of Changes. Princeton University Press, 1997, p.

xxx: “(…) the I-Ching is called upon when one sees no other way out.”; Immanuel Kant (1793). Die Religion innerhalb der

Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft, p. 50; pp. 57-64; p. 64, end of footnote.85 J.L.F. Gerding (2013). Filosofische bespiegelingen rond spiritualiteit, Universiteit Leiden, p. 3.

After Bruscia, the described method could be called descriptive, rather than diagnostic, interpretive, prescriptive, or

evaluative. See chapter 4 of Kenneth E. Bruscia (1998):Defining Music Therapy. Second Edition. Barcelona Publishers (USA),

See for examples of such experiences in literature Etzel Cardena (2010): Varieties of Anomalous Experience: Examining

the Scientific Evidence; William James (1902): The Varieties of Religious Experience.

Group sessions during lectures and art events are continued, however.

See chapter 6 (Intervention) of Kenneth E. Bruscia (1998): Defining Music Therapy. Second Edition. Barcelona Publishers

(USA), 1998.

Iebele Abel (2013). ICRL Technical Report 13.001.

Matthew D. Smith (2003). The Role of the Experimenter in Parapsychological Research. Journal of Consciousness Studies,

, no. 6-7, 2003, pp. 69-84.

Individuals’ reactions to their anomalous experiences can foster psychopathology and trauma. See for some in depth

information Berentbaum et al. (2001): Varieties of Anomalous Experiences: Examining the Scientific Evidence, (ed. Etzel

Cardeña, Steven Jay Lynn, and Stanley Krippner), Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2001, p. 35;

Chapter 4 of Pim van Lommel (2010): Consciousness beyond Life. The Science of the Near-Death Experience.New York:

Harper Collins, 2010; Denish Dutrieux (2004). Kundalini, Deventer: Ankh Hermes, 2004.

Henri Bergson (1932). The Two Sources of Morality and Religion. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame (Indiana),

, pp. 228-229.

Henri Bergson (1932). The Two Sources of Morality and Religion. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame (Indiana),

, p. 310.

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).